Introduction

The northwest Alaska town of Nome was the jumping off point for Russia for our reporting trip to Chukotka to cover the hunt for the gray whale. Back then, an Alaska carrier -- Bering Air –made sporadic charter flights for a brief 80-minute flight, and, in the summer of 2000, one of their aircraft whisked us from the northwestern edge of North America –across the international dateline – to northeast Russia.

The Bering Air flights were part of the broader opening – a melting of the ice curtain - that began in the late 1980s amid glasnost and the collapse of Communism. By the early 1990s, Russians could fly directly from the Far East cities of Magadan and Khabarovsk to explore Anchorage, where they often visited Costco to stock up on all kinds of merchandise then much harder to find in their own country. Scientists from both countries developed stronger networks for sharing information about marine mammals, bird populations and fish stocks. And U.S. conservationists worked with their Russian counterparts to boost protections for salmon-rich river systems on the Kamchatka Peninsula.

When we launched our reporting trip, Alaska-Russia ties were once beginning to be more strained. Putin had just come to power, and there were hopes that he would forge more ties to the West. Even then, it was not easy to get visas for the visit, and they were so limited in time that we feared they would expire before we got out on the whale hunt.

In the years that followed, relations chilled still further.

In 2019, I returned to Nome in 2019 on a reporting trip focused on climate change. By then, the Bering Air flights to Russia had faded into history. And U.S. marine biologists, amid a record-shattering marine heat wave that had upended the Bering Sea ecosystem, were struggling to understand the impacts in a Chukotka region where contacts with Russian scientists had withered.

In the aftermath of the February 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, U.S.-Russian relations have entered a deep-freeze. In September, 2024, the U.S. military briefly deployed more than 100 soldiers to the Aleutian Island of Shemya in response to a surge in Russian air and naval activity off Alaska.

It feels like an ice curtain has once again descended on the Bering Strait. I feel ever so fortunate to have been able to make that reporting trip to Chukotka back during the window of time when that short hop from Nome to Provideniya was still possible. And, I hope, someday, it will be again.

Hal Bernton

September, 2024

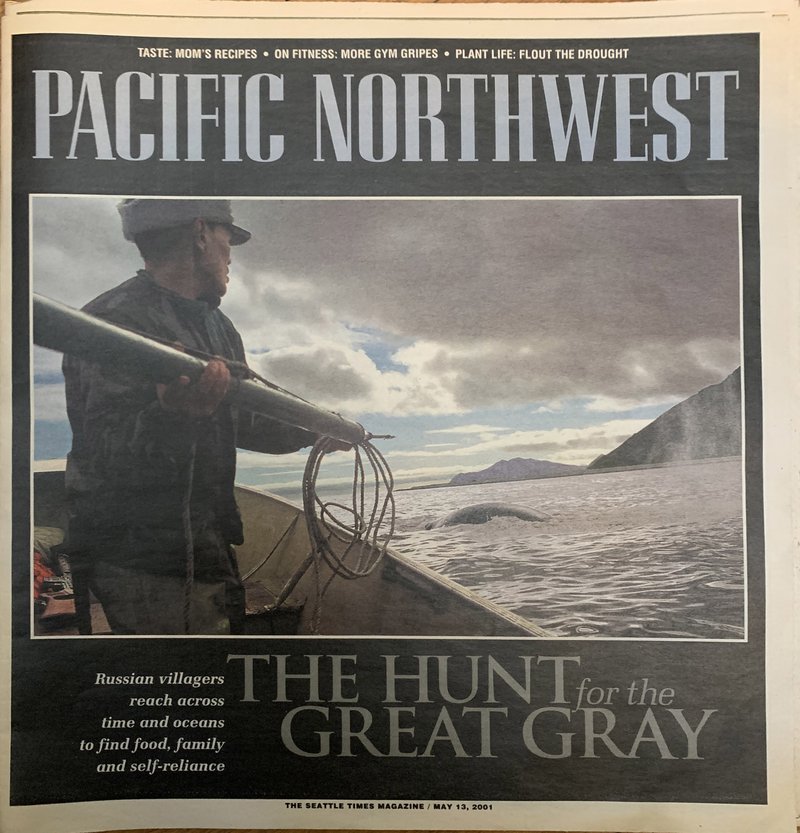

The Hunt for the Great Gray

In need of food, a destitute village revives ties to ancient kinsmen and the beast that binds them

Written by Hal Bernton

Photographed by Alan Berner

Originally published on May 13, 2001 in The Seattle Times Magazine

IGOR MAKOTRIK balanced in the bow of an aluminum skiff and aimed his rifle at a small gray. He was close enough to catch the rank odor of baleen-filtered breath. He hoped for a quick kill.

Back in the Eskimo village of Novoe Chaplino, his people were hungry. Store shelves held a few staples - rice, noodles, tea. But in the decade of deepening poverty since the collapse of communism, most villagers lacked the rubles to buy even those modest offerings. A single whale would feed most of the 400 villagers for as long as two weeks. Meat, skin, fat, liver, heart, tongue - even the whale's intestines would be washed and cooked.

A brawny hunter with the status of an elder, Makotrik was the best harpooner in the village and a crack shot. But he lacked firepower. His almond-sized bullets were better suited for hunting seals than slowing a 20,000-pound whale.

The gray exposed a flank. Three times, Makotrik fired. The bullets pricked the thick flesh, drawing spurts of blood. The animal rolled, then dove into the slate sea. Makotrik, with patience born of desperation, waited. When the whale resurfaced, he fired again - a battle played out over and over this blustery August morning. This whale would not die easy.

EACH SPRING, the 6,000-mile migration begins anew. Thousands of gray whales head north from calving lagoons off Mexico's Baja Peninsula. They glide in waves past California, Oregon and Washington to the shallow waters of the Bering Strait, where they spend summers scrounging the sea bottom for shrimp, crab, kelp and seaweed.

Early last century, the gray was hunted to the brink of extinction. An international ban on commercial hunts helped the population rebound - enough so the gray was removed from the U.S. endangered species list in 1992. Despite a recent downturn in births, they still number more than 23,000.

Two years ago, hunters from Washington's tiny Makah Indian tribe fired two shots from a high-powered rifle to kill a gray off the state's northwestern tip. For the Makah, the taking of the whale was seen as a triumph of cultural pride, a return to tradition that had lapsed for 70 years. But the hunt drew outrage from animal-rights advocates, and stoked a fierce debate about the ethics of modern whaling in the Pacific Northwest, where grocery stores bulge with abundance, science offers insights into the intelligence of sea mammals and younger Makah had lost the taste for gray.

As the gray migrates north up the Washington coast this spring, the Makah are poised to hunt again, with permission from the International Whaling Commission to take as many as five a year. But most of the whales will pass unharmed, targeted only by whale watchers. They will swim north to Alaska, into the food-rich Bering Strait. And some will continue west, beyond the cloak of the old Ice Curtain, to Russian waters. At the end of their migration, the whales offer a window into a world where the fall of communism has yet to bring a hint of capitalist affluence. The native peoples of Russia's far north have been pushed back to subsistence on a scale rarely - if ever - seen in modern times.

Here, more than 120 grays are killed each year in hunts revived not to keep a culture alive but to keep families alive.

CHUKOTKA IS the whalers' homeland, a Texas-size province tacked on the northeastern edge of Eurasia, where the continent reaches a ragged finger into the Bering Strait. More than 6,000 miles separate it from Moscow. But Alaska's mainland is as close as 53 miles - closer than Seattle is to Olympia. Most of Chukotka's 77,000 residents came from elsewhere in Russia, lured to the harsh north by the promise of Soviet-era jobs. About 11,000 are natives, many who live in a dozen coastal villages that pursue the gray whale. They are Chukchi, traditional reindeer herders who have turned to the sea for sustenance, and Y up'ik Eskimos, who share a whaling culture with all Alaska Eskimos and bloodlines with the Yup'ik from western Alaska and islands on the U.S. side of the Bering Strait.

In centuries past, the Yup'ik were one people who boated between settlements that spanned both sides of the strait. But Cold War ideologies divided the Yup'ik. Chukotka's coastline bristled with troops and weaponry; travel across the Bering Strait was banned. Though the strait reopened in the glasnost thaw, Chukotka remained a sensitive border zone. Foreign travel was tightly controlled, and through the 1990s aid from Alaska Eskimos to Russian natives was often resisted.

These restrictions shielded Russian whalers from the animal-rights protests that dogged the Makah. But they also obscured the hardships endured in one of Russia's most destitute regions. Alcoholism, pneumonia, tuberculosis and influenza have pushed male life expectancies among native villagers to under 50 years, a figure akin to Bangladesh. Remote village stores - stocked in Soviet times with cheap sausages, chickens and fresh fruit shipped in by the state - are near empty.

In the winter of 2000, some children were so weak they fainted at school. U.S. religious groups sent in tons of powdered milk, dried fruit and other foodstuffs - not enough to meet the need. "It was very difficult for the staff," said Nadezdha Gorbovtzova, principal of the Novoe Chaplino school. "For teachers to know that children were hungry, in really bad shape, and there was so little we could do to help."

Propelled by such hunger, Bering Strait villagers have turned back to the land and sea for as much as 80 percent of their diet. It's a hard way to go. Chukotka's broad, treeless valleys are divided by bare-rock mountains that reach to the coast and rise in sheer walls from the sea. Air temperatures in winter dip below minus 40 degrees; chill, damp winds blow through most of the summer.

From gravel spits, the natives harvest kelp and stake out nets to catch salmon and Arctic char. From small aluminum skiffs, they hunt ducks, sea lions, seals and walrus. And they pursue the gray, an undertaking that holds less political risk, but far more personal danger, than off the American coast. While Washington's Makah stalked their whale with high-powered weapons in the escort of Coast Guard vessels, the Russian natives last summer hunted from skiffs, with underpowered weapons and hand-thrown harpoons packed with homemade shells.

Grays are aggressive, apt to turn and charge when provoked. Several Chukotka whalers have died after tumbling into water cold enough to kill a man in 12 minutes. Still they hunt, in pursuit of the greatest subsistence prize.

Last August, Valentina Ettyn had nothing to feed her three children but gray. They breakfasted on salty whale jerky, snacked on chewy skin and fat known as muntaq, and boiled the meat with a garnish of tundra greens for dinner.

"We ate the whale from morning 'til night," Ettyn said.

THE JUMP-OFF point to Chukotka is Nome, Alaska, a turn-of-the-century gold-mining boomtown that now claims fame as the finish line of the Iditarod Sled Dog Race. A nine-seater, operated by Bering Air, flies west across the strait, touching down 80 minutes later in the Russian town of Provideniya.

The air link was established in 1988 with a "Friendship Flight" designed to reopen travel between the U.S. and Soviet Union. Alaskans who arrived on that first flight discovered a cluster of concrete-block apartments, painted in pastels, stair-stepping up a mountain.

Provideniya was then a thriving port of 5,000 souls, a promising new gateway for American commerce and tourism. Workers came from throughout Russia to service hundreds of ships that plowed up the Bering Strait to deliver supplies to Arctic communities. The town boasted a chicken farm, sausage plant, dairy and brewery that produced thick, brown beer.

But glasnost dreams were dashed when shipping traffic and Soviet subsidies ended. Only a handful of vessels stop at the port each year; one crane has been idle so long that a raven built a nest on top and hatched a brood of young. The population has shrunk to 2,000. Many of the pastel apartment blocks are abandoned, the windows smashed, the interior wallpaper torn into curling piles.

But as some flee, Eskimo and Chukchi natives move here, seeking relief from even bleaker conditions in their villages. Last summer, Genna Gotgyrgn came from Yankraynnot, a Chukchi village 50 miles north, after a winter eating little but fermented seal meat and huddling in a home with no electricity. "I used a whale-oil lamp for light," he said.

While there is no shortage of housing for such refugees, the Soviet-era heating and plumbing system is failing. Apartments are so cold in winter that coats are standard indoor garb and frozen toilets can't be flushed. "This is Russia, so people do what they must," said Ludmilla Gladkih, a radiologist at the town hospital. "They just go outside."

Lacking hot water, residents bathe at the municipal sauna, open twice a week each for women and men.

The stores in Provideniya still offer abundance - eggs, cheese, Washington's Golden Delicious apples and Yakima russet potatoes. But most here can't afford $2 to $4 a pound for sausage; work, when it can be found, brings in a scant $200 a month.

Gladkih, the radiologist, worked months last year without pay, in a hospital short of medicine, plastic gloves, syringes and bedding. Patients suffered a wide range of infectious disease and scurvy, an old sailor's scourge that weakens gums and loosens teeth due to a lack of vitamin C.

"People do not get enough fruits and vegetables," she said.

THE ONLY ROAD out of Provideniya winds north 18 miles, up the rocky flanks of the coastal mountains, over a pass, to Novoe Chaplino. The village is a poor place to launch a subsistence renaissance, tucked at the end of a deep-cut fiord, miles from the prime maritime hunting grounds.

Novoe Chaplino was built in 1959, when bellicose Nikita Khrushchev was Soviet premier and Cold War security - not hunting - was the paramount concern in Chukotka. Russian officials had ordered that the old village of Chaplino, which spread out on an exposed cape, be shut down as too vulnerable to the distrusted West. In its place, the Soviets erected a border-guard station to watchdog the coastal waters. Residents were moved to Novoe Chaplino, where boat travel could be more easily monitored.

Igor Makotrik was six months old when his family was transplanted here. His father was Chukchi; his mother a Yup'ik Eskimo with relatives on the U.S. side of the Bering Strait. Makotrik began taking his rifle to the tundra to shoot quail when he was 10. During his lifetime, the Soviets transformed rural life in Siberia. Potatoes, beets and wheat won't grow this far north, so villagers were assigned to work brigades according to their traditions: Chukchis tended reindeer for meat and hides; Eskimos hunted walrus. But under Soviet rule, the work was done for state-run farms. And much of the meat went not to families but to foxes, whose lush furs were in demand in Moscow and the West.

It mattered little if the farms made a profit, or if the brigades worked for wages rather than food. Subsidies were plentiful, and village stores bulged with cheap, imported food.

"Our lives were stable," Makotrik said. "We all received regular salaries. Our children went to boarding schools, and the Soviets told us everyone was headed toward a radiant future."

By the late 1980s, more than 20,000 foxes were caged in fur farms in Novoe Chaplino and nine other coastal Siberian villages. When the supply of walrus meat proved inadequate to feed the foxes, the state farms called in a large whaling ship - the Zviozdny - each summer. Armed with powerful antitank guns, they would take as many as 169 grays a year - the number allowed by the International Whaling Commission. The commission approved the harvest "for the needs of the Native population." But like the reindeer and walrus, whale meat mostly went to the foxes.

The collapse of the Soviet Union brought an end to all but one of the fox farms. The demand for fox feed waned, and the industrial whaler stopped coming. Novoe Chaplino became home to ghost towns of weathered, empty fox cages perched on platforms at the edge of town. The village beach is a graveyard of the half-buried skeletons of slaughtered grays. A rendering plant, where blubber was boiled into industrial oil, rusts just beyond the tideline.

IN MOSCOW, the death of the Soviet state gave birth to a dizzying new world where the super-rich drive Mercedes Benzes and party at opulent nightclubs. In Novoe Chaplino, it forced the villagers back in time. They could risk starvation - or return to the traditions of their ancestors.

Makotrik, 42, is a leader in the native whaling resurrection, and heads his village's 10-man hunting brigade. He's a quiet man, slow to anger, who enjoys novels about the early days of Russia. He and his wife, Ludmilla, live in three rooms of a barracks-like building made of plaster-coated logs. The interior walls are papered but bare of personal adornment. Water comes from three barrels filled at a nearby river.

Even with the changes, Makotrik works for the same old bosses. The Soviet state may be dead, but the state farm lives on, renamed an "agricultural enterprise." Where once it employed men to hunt for fox food, now it pays them to harvest whales and walrus for people.

But the state farm is almost broke, and often fails to provide essential gear for the hunts. So Makotrik and other native leaders have turned to American Eskimos for help.

Alaska's St. Lawrence's Island lies 36 miles off the cape of old Chaplino, close enough to watch the sun rise over the rugged Chukotka coastline to the northeast.

The Yup'ik Eskimos who live on St. Lawrence are not wealthy by U.S. standards. Their small cash economy comes from government jobs and traditional walrus ivory carvings. But over the past decade, they have given freely to their Russian kin, sending clothing, fish nets, outboard motors and skiffs, including the 16-footer that Makotrik and his son-in-law, Maxim Agnagiffyak, use to hunt whales.

The Alaska Inupiat also have helped, especially in providing arms for Russian whaling. The Inupiat homeland, on the Alaska's North Slope, encompasses the rich Prudhoe Bay oil fields. By taxing the oil companies, the Inupiat-controlled local government - the North Slope Borough - has collected hundreds of millions of dollars. The high school boasts an indoor swimming pool. An Arctic college was built. In Barrow, the largest town on the North Slope, supermarkets fly in frozen lobster tails and fresh kiwi.

But whaling remains the heart of Inupiat culture. They hunt the bowhead, which is bigger but slower and less aggressive than the gray. As the bowheads cruise past Barrow each spring and fall, Inupiat politicians and businessmen abandon their desks and head to sea, carrying cell phones along with their weapons.

The Inupiat sent a delegation to Chukotka's villages in 1994 and, in the past decade, have financed more than $4 million in aid to the province. They've sent boots, tools and raingear, and funded native hunting associations to operate independently of the government. They've worked with the U.S. National Park Service to bring Makotrik and other Russian hunters to Barrow to share information about marine life. And, fighting through Russian red tape and official resistance, they've sent hunting weapons. In 1997, the aid shipment included 20 dart guns and 100 exploding projectiles. Mounted at the end of a harpoon, the guns are far more effective against whales than Russian rifles.

But when the time came for last summer's hunt, the projectiles had been used up. Bureaucratic delays kept a new shipment from reaching Chukotka until February.

AS MEAT SUPPLIES dwindled, other problems plagued the summer hunt. Makotrik's brigade hadn't drawn a full month's salary in more than a year. They sometimes lacked money to buy bread - much less a bit of jam - to go with their tea rations.

Gasoline shortages were chronic and acute, often idling the hunters for days. When a government shipment of fuel failed to arrive, state farm official Nikolai Mitrophanov scrounged three tons of gas; 15 tons were needed.

Desperate for revenue, the state farm tried to sell walrus and whale meat to hungry villagers. An 88-pound cut of gray was priced at 1,200 rubles, or about $40. Villagers had to buy on credit. Mitrophanov, a tall man with a drooping moustache, says it was easier in the old days when the government provided ready supplies and cash. His office wall sports a small red-and-gold banner with a hammer and sickle, an image of Lenin and this adage: "We come to the victory of Communist labor."

Makotrik shares no such nostalgia. Despite the hardships of the present, his visit to Alaska offered a glimpse of a better future. There, he met Eskimo people with money, political power and a swagger to their step.

"They behave as masters of the land," Makotrik said. "We do not feel as masters of our land, not yet."

In early August, Makotrik gathered hunters from several villages. With support from an independent native group, funded with money from Alaska, they bought gasoline and went to sea, where they killed a small gray. In defiance of the state farm, they gave away most of the meat.

"People need to eat, and they can't afford state prices," Makotrik said.

As the whale was hauled on the beach to be butchered, dozens of families came to claim a share. But what the people saw as a triumph, state farm officials saw as insurrection. The hunters were summoned to Mitrophanov's office. The giveaway had robbed the state farm of sales revenue, officials fumed. Each hunter must pay 2,700 rubles in compensation.

Makotrik wanted to quit the brigade in protest. But he would have to return his rifle to the state. Where would a hunter be without a gun? And where would his people be without meat? The gray caught in early August was gone. Ettyn, the village woman raising three children, had only flour and sugared tea. Her 1-year-old daughter drank thin tea from a baby bottle.

SQUALLS FROSTED the mountain peaks with a thin rime of snow as Makotrik's brigade piled into the back of an old pickup. They bounced north for 15 miles on the barest trace of a route that wound through a mountain valley, over another pass, and at times vanished underwater as it traversed a cobbled beach.

It took an hour to reach the hunting camp, a stout-walled wooden barracks beside a strait within a strait. The larger of the straits is the Bering, which separates northeast Asia from North America. A second, much narrower strait is formed by the Russian mainland and several rock-walled islands a few miles offshore. In the summer, it is visited by thousands of grays. From the front porch of the barracks, hunters and their families can watch as the whales spout, roll, dive and rise to spout again.

It is a stunning display of whale abundance. Yet the past two years have brought puzzling trends: biologists noted a plummeting number of births from the Mexican calving grounds, an increase in the number of whales grounding on U.S. beaches and sightings of whales thin to the point of emaciation. Marine biologists wonder if, as grays rebound, this is part of a natural culling; or perhaps their food supply has slumped because of climatic changes.

In Chukotka, the concerns are far from academic. Whalers have encountered a number of "stinky whales" - animals with a peculiar medicinal odor. In 1999, 10 harvested whales were so foul that Russian villagers fed them only to their dogs. Scientists have not yet tested to determine if the odor is a byproduct of malnourishment or of chemical contamination. To ensure food for his people, Makotrik relies on his nose. He avoids striking any whale that smells of medicine rather than the sea.

ON THE EVE of the hunt, the mood in camp was festive. Hunks of walrus sizzled outside on an open fire, stoked by driftwood and boards torn from the fox cages. Inside, coal-fired stoves toasted the barracks to a cozy warmth. Children scurried about as a small transistor radio hooked to a large antenna picked up a station from Nome: Neil Young, Paul Simon, the Eagles' "Hotel California." The newsbreak announced that Richard Hatch had won $1 million for outlasting other contestants on a tropical island in TV's "Survivor."

As the light faded, the families gathered to feast on walrus. Slabs of breast meat, rich and oily, were laid on the table boards, along with a pile of gristly joints.

Makotrik ate quickly, then retired to a bunkroom. He checked the steel-shanked tips of the harpoons mounted on stout wooden poles. They would be hurled by hand in the initial attack, attached to colored buoys to track the whale and later keep the carcass afloat.

Washington's Makah made their first strike by harpoon. But once it buried itself in the whale, the Makah fired two .57 caliber shells from a high-powered rifle to finish the kill. First strike to death took 8 minutes.

Makotrik had only his hunting rifle for the second line of attack. He had run out of solid steel ammunition, so he would fire softer, copper-jacketed bullets, with just one-tenth the strike force of the Makah ammunition.

His third line of attack was an Alaska darting gun mounted on a harpoon. The 19th-century gun is designed to unleash a black-powder projectile that explodes in the whale's flesh on impact. When all goes well, death can come 15 minutes after the first harpoon strike.

But a shipment of projectiles from Alaska hadn't arrived. Makotrik spread pipe and steel-wool packing on a table next to his bunk, and fashioned his own rude projectile. His shell would not explode, but drive into the whale like a huge nail.

DAWN BROKE to Carlos Santana on the radio. The winds had eased, and sunbreaks teased through a high overcast. After a few cups of hot tea, the hunters hopped into three small skiffs - gifts from Alaska - and took to the strait.

Makotrik rode in the smallest skiff, driven by his son-in-law. He wore an Alaska cap and sweatshirt, but no lifejacket. He stood in a boxer's crouch, knees flexed, shoulders hunched, harpoon in hand.

He spied a spout. The skiff raced toward the spray, motor humming like an angry bee. The whale dove before Makotrik was close enough to throw.

Whales spouted all over the strait. The hunters gave pursuit, dozens of times, only to meet water. Finally, a harpoon bit into a slow-moving gray.

It was no more than 30 feet long, far smaller than the 50-plus feet some grays reach. Yet it was larger than the skiffs, strong and full of fight. The harpoon did little but irritate it. As it raced up the strait, the hunters held back with a caution born of hard experience. In 1996, a whale flipped a boat of hunters from the village of Nulingran, killing three. More recently, a gray whale crushed a boat from the village of Laverntiya. The hunters dumped into the ocean were lucky to have rescue near.

Makotrik waited for the whale to tire, his skiff pacing it like a matador toying with a bull. He hurled a second harpoon. Two harpoons from the other skiffs found purchase.

Still, the whale showed no sign of slowing. It spouted a clear spray of salt water and reversed into open, rougher water. Makotrik's hunters grabbed their rifles. They fired at the flank. They fired at the back. They moved in and fired at the barnacle-encrusted head.

The gray turned and charged.

Makotrik's son-in-law steered away sharply, knocking Makotrik to the floor of the boat.

The whale shook off three of the harpoons and threatened escape. Makotrik struck again, his harpoon now tipped with the darting gun. The whale rolled, its breathing labored. Then it found a last burst of energy, swimming east along an island on the far side of the strait.

Makotrik threw another harpoon tipped with the darting gun, and struck the base of the whale's head. Blood spouted from the blow hole and fell into the sea in a crimson slick.

NATIVE TRADITION holds that a moment comes when a whale offers itself up to its hunters. The gray was finally dying, just off a beach that held rows of upright bones, a shrine to generations of past kills.

Even by Chukotka standards, it was a long hunt. In 1999, the average kill took an hour and 25 rounds of ammunition, according to documents submitted to the International Whaling Commission by Russian officials. To kill this small gray, Makotrik's hunters spent three hours, four harpoons, more than 100 rifle rounds and two shells from the darting gun.

WHEN THE MAKAH killed their gray, the crew prayed, then cheered, as the Coast Guard escort vessel kept protesters at bay.

There was no protest to greet Makotrik's brigade. And no celebration. Just the relief of a job near-done. As the whale struggled against the inevitability of death, the hunters tethered their skiffs together, shared a thermos of tea and waited.

When it was over, they tied a rope to the whale's tale and, together, towed the carcass back to camp.

A crowd waited on the beach, some to watch, most to work. They set on the whale with knives the size of small swords. They carved skin and blubber into thick blocks weighing 50 pounds or more. They sliced fillets of burgundy steaks. They sawed off meaty bones like giant spareribs. They sliced out the tongue - longer than a man's body - and set it aside as a delicacy.

They worked quickly, and with confidence. There was little talk - just the sound of knives scraping against stones as they prepared for the next round of cuts.

Postscript

VILLAGERS TOOK one more whale before the ice set in and the grays turned south. Snow in the winter months piled in drifts more than 6 feet deep. Diesel fuel was in short supply; in Novoe Chaplino, electricity was rationed to three hours a day.

But the winter also brought hope. In January, the province of Chukotka, so long frozen out of the dreams of a new Russia, inaugurated a new governor. A rich young oilman from Moscow, he promised to open links to the West, pay workers on time and restore food shipments to the villages.

Subsistence, however, remains vital to a people hungry for self-reliance. This summer, native whalers will return to the sea. Aided by a new shipment of whaling weapons from Alaska, they are expected to take more than 120 grays.

Introduction

The northwest Alaska town of Nome was the jumping off point for Russia for our reporting trip to Chukotka to cover the hunt for the gray whale. Back then, an Alaska carrier -- Bering Air –made sporadic charter flights for a brief 80-minute flight, and, in the summer of 2000, one of their aircraft whisked us from the northwestern edge of North America –across the international dateline – to northeast Russia.

The Bering Air flights were part of the broader opening – a melting of the ice curtain - that began in the late 1980s amid glasnost and the collapse of Communism. By the early 1990s, Russians could fly directly from the Far East cities of Magadan and Khabarovsk to explore Anchorage, where they often visited Costco to stock up on all kinds of merchandise then much harder to find in their own country. Scientists from both countries developed stronger networks for sharing information about marine mammals, bird populations and fish stocks. And U.S. conservationists worked with their Russian counterparts to boost protections for salmon-rich river systems on the Kamchatka Peninsula.

When we launched our reporting trip, Alaska-Russia ties were once beginning to be more strained. Putin had just come to power, and there were hopes that he would forge more ties to the West. Even then, it was not easy to get visas for the visit, and they were so limited in time that we feared they would expire before we got out on the whale hunt.

In the years that followed, relations chilled still further.

In 2019, I returned to Nome in 2019 on a reporting trip focused on climate change. By then, the Bering Air flights to Russia had faded into history. And U.S. marine biologists, amid a record-shattering marine heat wave that had upended the Bering Sea ecosystem, were struggling to understand the impacts in a Chukotka region where contacts with Russian scientists had withered.

In the aftermath of the February 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, U.S.-Russian relations have entered a deep-freeze. In September, 2024, the U.S. military briefly deployed more than 100 soldiers to the Aleutian Island of Shemya in response to a surge in Russian air and naval activity off Alaska.

It feels like an ice curtain has once again descended on the Bering Strait. I feel ever so fortunate to have been able to make that reporting trip to Chukotka back during the window of time when that short hop from Nome to Provideniya was still possible. And, I hope, someday, it will be again.

Hal Bernton

September, 2024