It Took 77 Years to Become the Woman She Wanted To Be

by April Saul

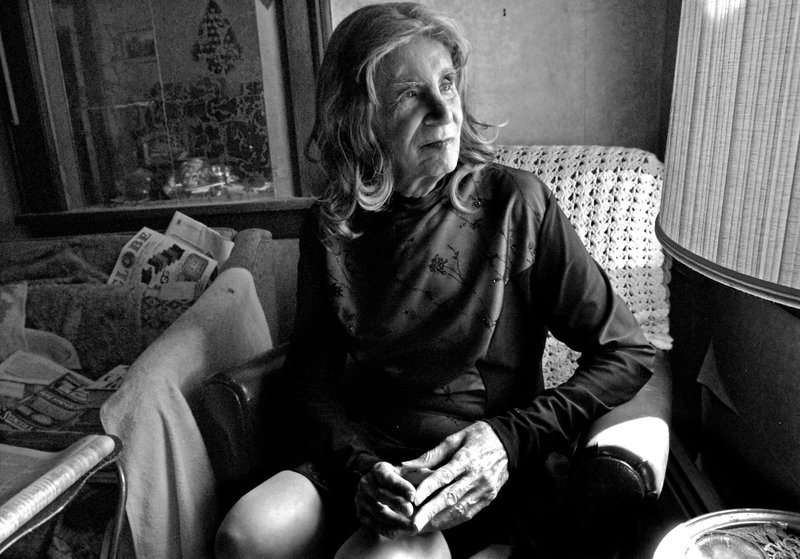

Wearing slacks, Mary Janes and a honey-blond pageboy wig, 82-year-old Renee Ramsey drives her old Chevy past the Dollar General and the Piggly Wiggly in Summerville, S.C., chatting her way through the routine errands that now bring such joy.

“They call me ma’am!” she says with pride. “Here, they treat me like a lady.”

At Food Lion, a fellow shopper calls out, “Hey, New Jersey!” — a reference to Ramsey’s Garden State roots.

“Renee makes your day,” says Katie Frink-Johnson, a deli manager at the Publix Super Markets. “She’s a sweetheart. ... We are what we are, and if you’re happy, I’m happy with you.”

There was a time when Ramsey was not at all happy. In fact, she was miserable, living an inauthentic life, known to all as Richard, and hopelessly trapped in a male body that did not feel like her own.

Then, five years ago, at the age of 77, Richard Ramsey underwent gender reassignment surgery and became Renee. The craggy-faced retired Navy veteran, who had spent most of his leisure time hanging out at American Legion and VFW halls in New Jersey, became an older woman with an easy laugh and gangly gait. Dresses, blouses and wigs replaced the old Army uniform Ramsey was fond of wearing.

Eventually, Renee Ramsey settled in South Carolina, where today she lives quietly, and quite happily, in a small town outside Charleston. Just another typical older woman, except, that is, for the remaining forearm tattoo that reads, “Death Before Dishonor.”

Ramsey is likely one of the oldest people in this country to undergo male-to-female gender reassignment surgery, but she is hardly alone. In May, Medicare announced it would begin covering gender reassignment surgery. Two months later, President Obama signed a bill giving employment protection not only to gay federal workers, but also to transgender men and women.

One of the reasons for the surge of attention to transgender rights has to do with the inroads neuroscience is making. Researchers now say that gender identification is something that happens in the brain of a fetus weeks after the sexual organs have differentiated into either male or female.

Sexual anatomy and gender identity, therefore, are both products of the brain and are the result of two different brain processes. (Sexual orientation is a third.) And brain processes, we now know, especially in a developing fetus, can be affected by myriad genetic and environmental influences. Just like sexual attraction, these scientists say, gender identity isn’t something we choose. It’s something we’re born with.

Growing up in Little Ferry in the 1930s, young Richard Ramsey had one simple, heartbreakingly unattainable dream.

“I would go to bed hoping that when I woke up, I’d be a girl,” Ramsey recalls. “And then, I’d wake up and look down and be so disappointed.”

The little boy who hated the sailor suits his “Pop” made him wear — and who helped his mom with cooking and sewing more than either of his two sisters — would not get his childhood wish for many years.

Transgendered individuals can undergo several surgeries. Here, Ramsey awakens following breast implant surgery in 2012.

Ramsey says she knew as early as age 4 that she was different. She felt “more like a sister than a brother” to her siblings. As a teenage boy, Ramsey shunned athletics and hated gym. One day, when her mother caught Ramsey wearing women’s underwear, he was taken to a psychiatrist. The sessions devastated the young boy because the doctor insisted it was just a phase that would pass.

Ramsey joined the military in 1951 “to get out of the house,” and remained on active duty as a 3rd Class Boatswain until 1963. During that time, Ramsey says, she was detached from the Navy on occasion for duel service in special operations with the Army.

“The only reason I went into the military was that I was hoping it would help me become more masculine than feminine.”

But the womanly feelings never dissipated.

“I felt so much like a female, that I’d get up an hour-and-a-half to two hours before everyone else to shower and change because I was embarrassed.”

In spite of having no real sexual attraction to women, Ramsey says, there were two marriages. The first was in 1953 at age 22, which ended in divorce after 20 years. Ramsey says that when her wife discovered her dressing as a woman, she moved across the country with three of their daughters (a fourth died during childhood), never to be seen again.

“They didn’t want to talk to me. … They didn’t want to have anything to do with me. It was unhappy,” she says. “My whole past was unhappy.”

Ramsey met her second wife, a widow named Vesla, at an American Legion convention and they married in 1982. The couple moved into Vesla’s house in Wallington, in Bergen County.

Once again, Ramsey’s wife discovered her dressing in women’s clothing.

But Vesla did not leave. “She tolerated it. We had an understanding that I wouldn’t do anything about changing as long as she was alive.”

It wasn’t until Vesla developed Alzheimer’s disease and was living in a nursing home that Ramsey began to consider having the surgery she had wanted all her life.

“I didn’t want to break my commitment to her, even if she didn’t know who I was,” she says.

So, it wasn’t until 2007, when Ramsey was told Vesla would not live much longer, that she began planning the transition. Vesla died in March 2009 and three months later Ramsey finally underwent gender reassignment surgery.

“When I had the surgery. I woke up and said, ‘I’m a lady.’ ”

Transgender refers not just to people who have undergone partial or full gender reassignment surgery, but to anyone who identifies as being the opposite sex of the gender assigned at birth.

Statistics on the number of Americans who identify as transgender are difficult to come by because few large-scale population surveys, including the federal census, have sought to tease out the number of transgender people from the general LBGT community. But several recent studies, including one by UCLA’s Williams Institute on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Law and Public Policy at its School of Law, put the number at about 1.5 million American adults.

Sherman Leis, a plastic surgeon in Bala Cynwyd, Pa., has been Ramsey’s doctor and confidant for the past six years.

During his 40-year career, Leis, who specializes in cosmetic and reconstructive surgery, has performed several hundred gender reassignment surgeries. He says he wants to help as many transgender people as possible, but it hasn’t been easy to find hospitals that will allow him to operate.

“I’ve been turned down at multiple hospitals in Philly,” he says. “They say, ‘We’d love to have you on the staff. You can do anything — except transgender surgery.’ ”

But Leis believes his practice, the Philadelphia Center for Transgender Surgery, saves lives.

“Seventy percent of transgender people have suicidal thoughts and 40 percent attempt suicide,” he says. “After successful transition, most people in the field believe the rate drops to about 8 percent for suicide attempts.”

Leis says that most of his patients are already taking antidepressants when they first come to him for help, having suffered “a lot of discrimination.” And patients such as Ramsey “have more of a rough time in blue-collar communities,” where there is less tolerance for alternate lifestyles.

For Ramsey’s “bottom surgery” in 2009, the doctor reconfigured the male genitals into female genitalia. During the next three years, Ramsey underwent feminizing procedures, including a face-lift and breast implants.

Following each surgery, Ramsey recovered in one of the small apartments at Leis’ office complex.

She paid for the operations — which cost about $25,000 total — with money she had saved over time. The breast implants, however, were a gift from a younger transgender woman she met by chance at Leis’ office, and with whom she still stays in contact.

“I said, ‘Thank you very much, but I’ll have to pay you back.’ She said, ‘No, that’s what sisters are for.’ ”

In a final 2013 visit to her former home in Wallington, Renee Ramsey, right, packs up some belongings, with the help of roommate Miranda Rights, to take back to South Carolina. On the wall is a photo of Renee when she was 9-year-old Richard, which she chose to leave behind.

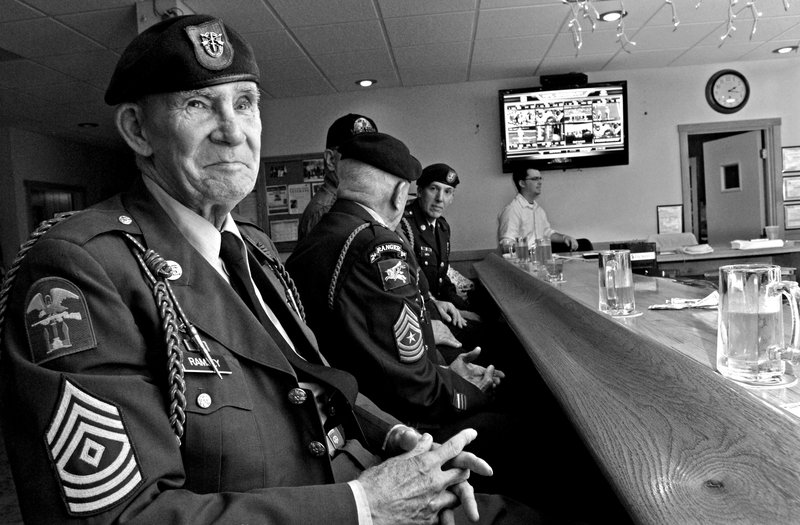

In the fall of 2009, several months after gender reassignment surgery, Renee Ramsey sat on a barstool, as always, at the American Legion Joyce Kilmer Post 25 in Milltown, wearing a color guard Army uniform and drinking a beer.

Having long deferred to the wishes of her parents and wives, Ramsey now had to decide whether to reveal the transition to her fellow veterans — or avoid the issue by embracing both genders.

Initially, she chose the latter course.

At veterans’ events, she remained Richard Ramsey, complaining privately, “It’s just like, ‘Don’t ask, don’t tell.’ ”

When she finally told her closest veteran buddy about the gender surgery, the man said he would not be seen with her if she dressed as a female. The rebuke stung.

“He said he didn’t want to be around me unless I was dressed like a man. He still doesn’t call me Renee,” she says.

At home, Ramsey began to dress as a woman, eventually getting the nerve to wear miniskirts to the Wallington bars that she called her “watering holes.” Though some patrons stared and seemed to be making fun of her, she remained a regular patron.

“Drinking was my way of coping with being lonely and being hurt. There was nothing else to do, no place to go.”

Clinical psychologist Jeanne Seitler, who practices in Ridgewood, began seeing Ramsey in August 2007, encouraging her to live in both worlds for a while. Seitler, who at their first meeting was struck by Ramsey’s contradictions — the gruff voice and a walk “like Olive Oyl” paired with “a pretty, fine-boned face” — worried about Ramsey losing the social outlet of the military social clubs — or worse.

“We didn’t know if she would be hurt, or murdered, or lose her benefits,” Seitler says. “We talked to a lot of people who said, ‘Lay low. Bind yourself. Put on your uniform. Go as Richard and have a good time. And when you’re back home, be Renee.’ ”

While the military is more accepting of gay service members, with the repeal of “Don’t ask, don’t tell,” it remains fraught with peril for transgender individuals who are excluded from service by the military medical code.

The situation improved in 2011, when the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs issued a directive guaranteeing that transgender veterans be provided hormone therapy, mental health care and pre- and post-operation care associated with gender reassignment surgery; everything, in fact, but the surgery itself.

Ramsey continued faking her way through VFW and American Legion halls. But when she wasn’t downing beers with the vets at the bar, she was taking classes at Le Femme Finishing School to learn how to dress and act more like a woman.

Ellen Weirich, working out of her Piscataway home, teaches transgender women and cross-dressing men how to be more feminine. Weirich, whose professional name is Lady Ellen, supported Ramsey, even driving her to the gender reassignment surgery.

“Teenage girls don’t find their style immediately,” Weirich says. “So what (men are) doing, when they start cross-dressing as a woman, is going through the teenage girl years.”

For example, Weirich tried to gently rein in Ramsey’s propensity for short skirts and garish makeup.

But after attending Le Femme events such as pageants, swap meets and shopping trips for several years, Ramsey stopped visiting the school. Once again, she felt out of place. This time, it was because most of the clientele at the school were cross-dressers rather than people who had gone through gender reassignment surgery.

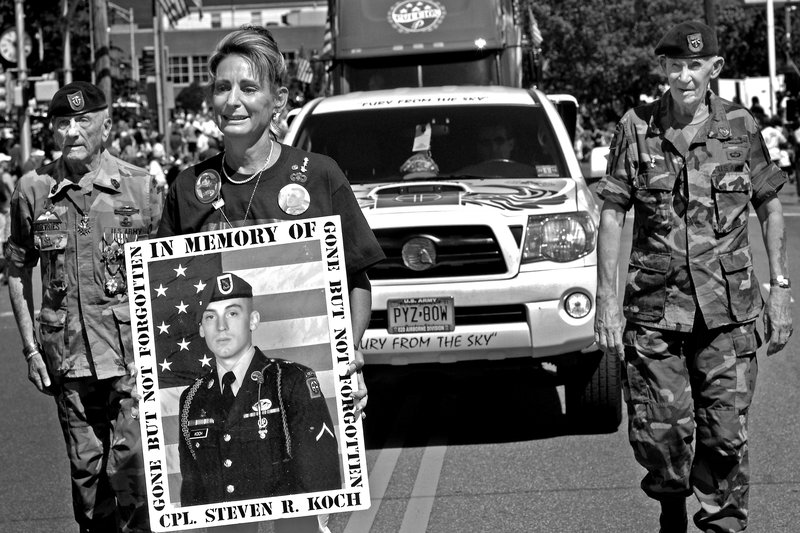

In 2012, new breasts and a new friend propelled Renee Ramsey to a new place. Now, her military shirts no longer fit — because of the breast implants, ending her appearances at the veterans’ events she had eventually come to dread.

“That was the end of my paradin’ days!”

Today, Renee Ramsey, left, lives with roommate Miranda Rights in South Carolina. "She's given me love and understanding. And helped me to see that I can't be afraid to be a lady," Ramsey says.

A mutual friend introduced Ramsey to Miranda Rights, a 55-year-old Brooklyn native who had been living as a bisexual female for the past 20 years. They began communicating by email. Rights, an aircraft quality control inspector, was a military veteran, like Ramsey, who also felt she was female from a young age.

Rights says that when Ramsey came to visit her in South Carolina for the first time in July 2012, she was not what Rights expected.

“I thought that I was going to have this frail 80-year old lady coming off the train. Then I realized I better get more beer in my house because this lady’s gonna drink me under the table!”

For Ramsey, the relationship with the ebullient Rights — whose hobbies include playing the drums and ice hockey, and shooting her semi-automatic rifle with a pink handle at the gun range — was a turning point.

The budding friendship emboldened Ramsey to dress as a woman during the two weeks that she was in South Carolina and to continue doing so when she returned to New Jersey.

“We’re like sisters,” she says of Rights. “She’s given me love and understanding. And she helped me to see that I can’t be afraid to be a lady.”

Unlike Ramsey, Rights has warm relationships with her siblings, children and an ex-wife, who calls her “Lady Gaga.”

Still, she is moved by Ramsey’s devotion to her and has become attached to the older woman as well.

“It’s sad to think that here’s someone who’s 82 years old and I’m at the top of the list,” she says. “It makes me realize how lucky some of us are to find love and be loved.”

Ramsey decided to move to South Carolina and become Rights’ roommate. They now share a small home in Goose Creek.

During Ramsey’s final visit to her old Wallington home, with Rights by her side, she tried to figure out how much of her stuff she could cram into her friend’s Audi for the long drive south.

It was easy to leave many of the family photos, she says — especially the framed portrait of a toothy, skinny, 9-year-old Richard Ramsey.

“They reminded me of who I wasn’t allowed to be.”