Farm Crisis

America's Farm Crisis

by David Peterson

Photographed over several months in 1986

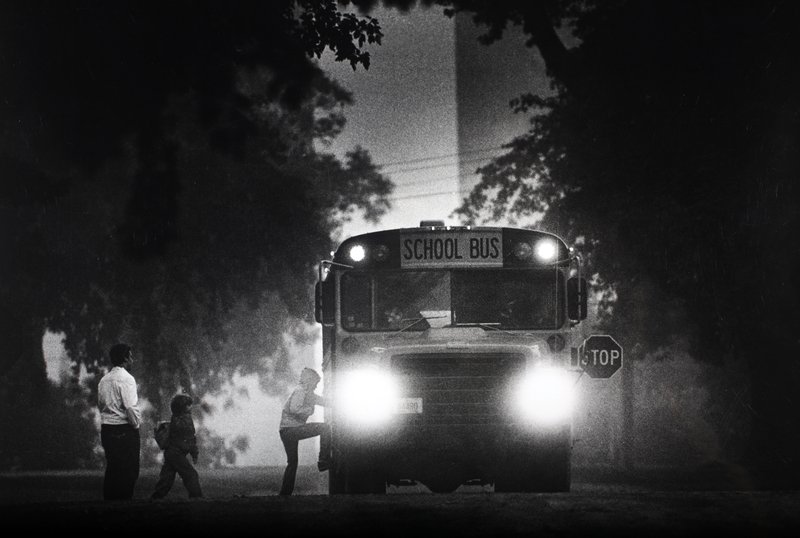

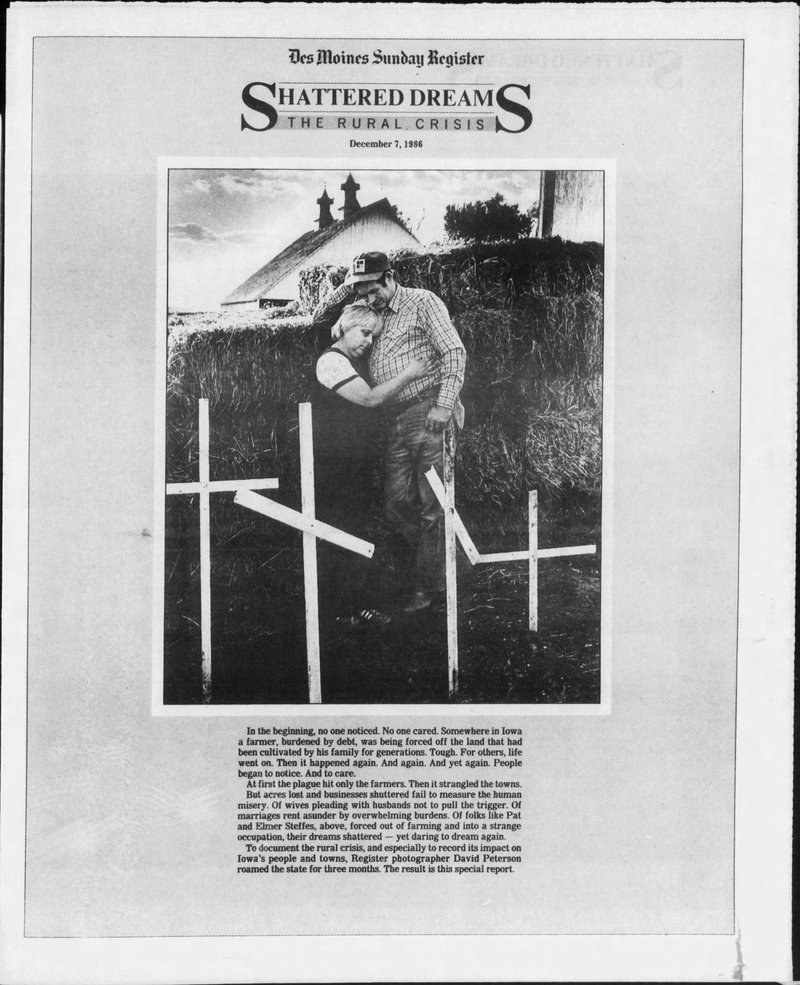

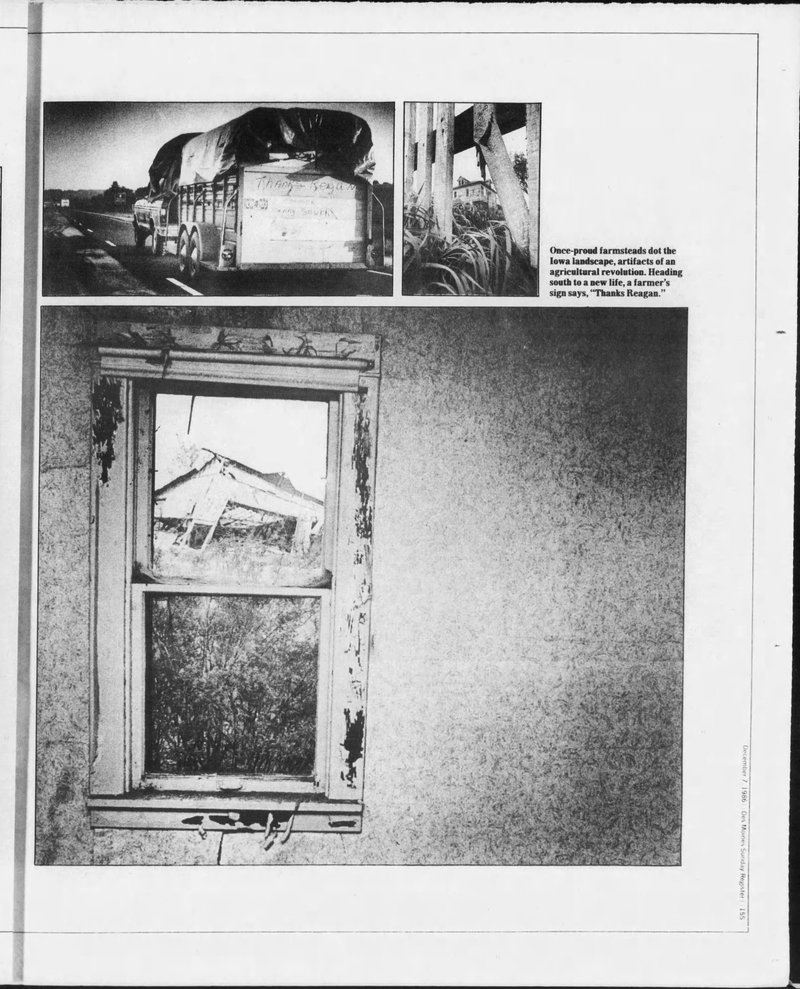

In the beginning, no one noticed. No one cared. Somewhere in Iowa a farmer, burdened by debt, was being forced off the land that had been cultivated by his family for generations. Tough. For others, life went on. Then it happened again. And again. And yet again. People began to notice. And to care.

At first, the plague hit only the farmers. Then it strangled the towns.

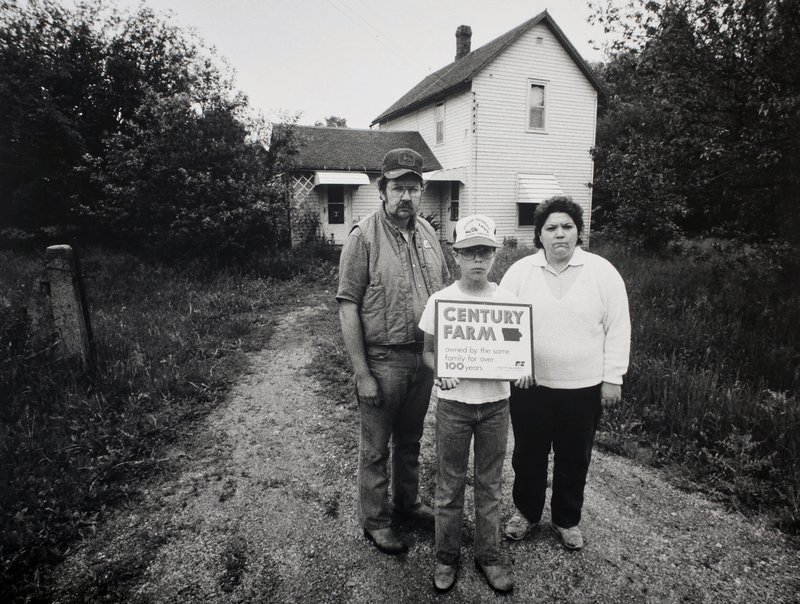

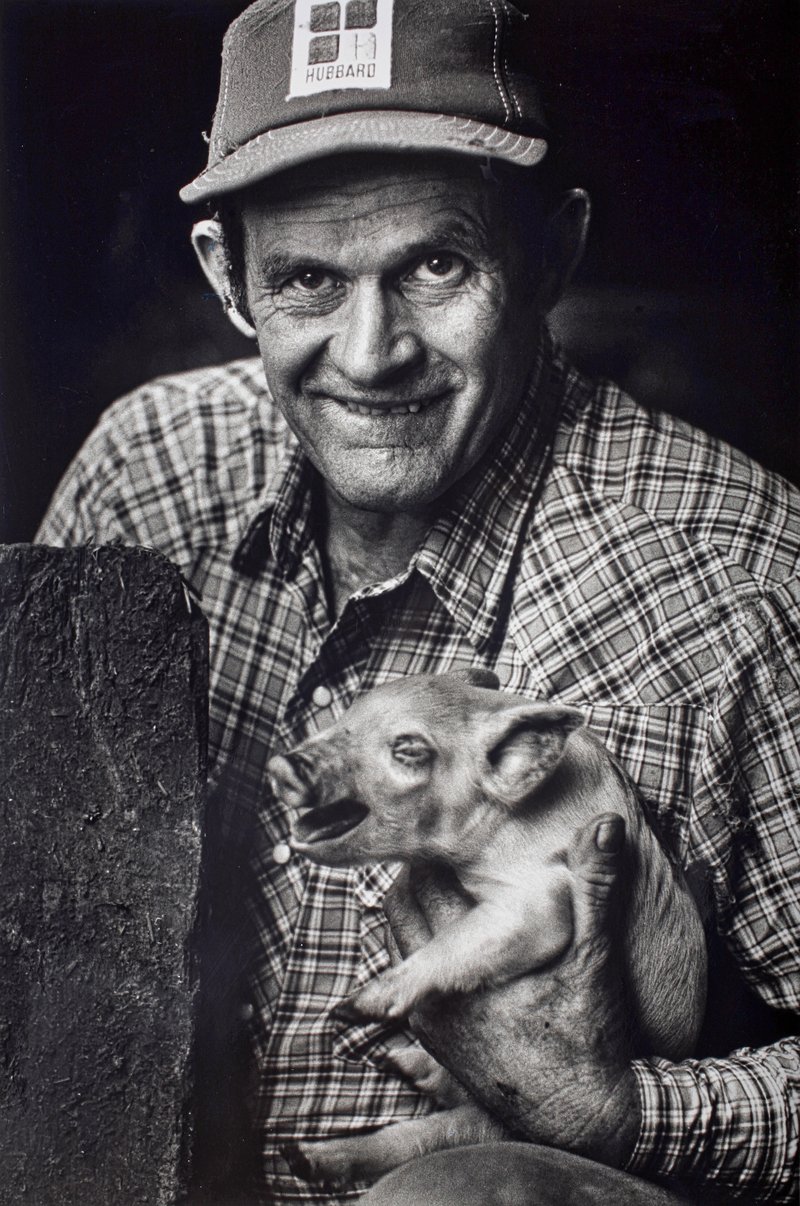

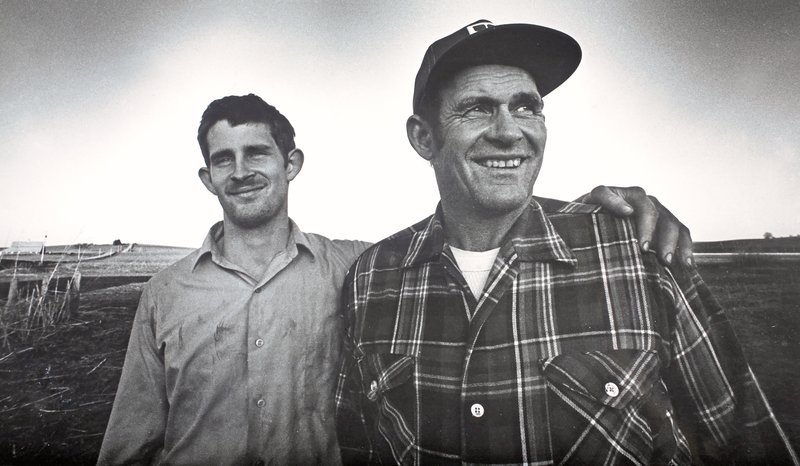

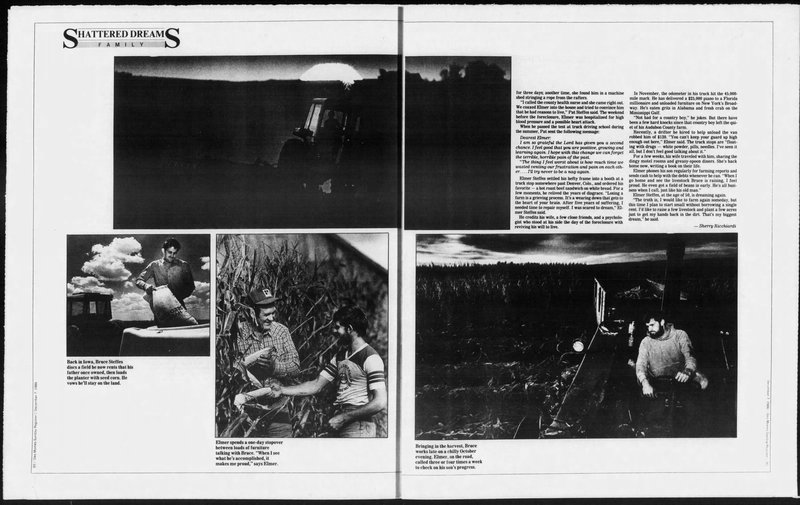

But acres lost and businesses shuttered fail to measure the human misery. Of wives pleading with husbands not to pull the trigger. Of marriages rent asunder by overwhelming burdens. Of folks like Pat and Elmer Steffes, above, forced out of farming and into a strange occupation, the dream shattered – yet daring to dream again.

This photo essay documents the rural crisis, and especially to record its impact on Iowa’s people and towns. -- by Sherry Ricchiardi

The Devastation Permeated Rural America

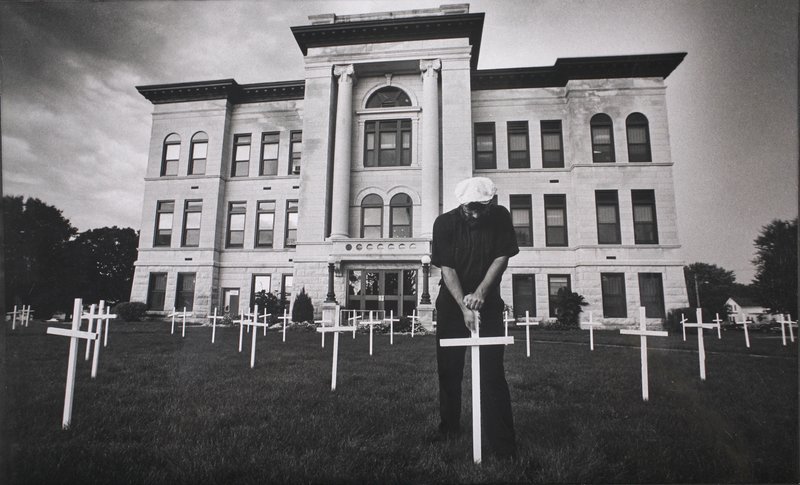

Visitors who Frank Cordaro’s home in Logan are greeted by a sign that says, “Farms Not Arms.”

The bearded priest pours a glass of sparkling water, then settles his muscular frame into a chair and begins the litany: “I just keep putting crosses in the courthouse yard and saying, “Folks, when are you going to put up a fight?” I’m hoping after harvest we’ll see some action. The spark, the intensity isn’t there. So many farmers are numbed out,” he said.

“I will work with anyone losing farm equipment or land in no-violent resistance. I will be arrested with them.”

On the day of the forced farm sale, the priest gathered up the 75 wooden crosses he’s nailed together and heads for the Harrison County Courthouse. Rain or shine, he shoves all 75 of them into the earth. “The crosses represent the sheriff’s sales we’ve had in this county since Ronald Reagan became president – that’s 75 sales compared to 12 in the previous five years,” said Cordaro, pastor of St. Anne’s Church in Logan.

“There are homes and businesses on the auction block, too. We’re seeing the death of the heart of our rural communities.”

Farmers resist non-violent civil disobedience, Cordaro believes, because “they are church-going people; they don’t have it in their guts to do this kind of confrontation.”

“Years ago, these people were standing on farms with equity for future generations. Now they are reduced to relocating pigs and cows in the middle of the night so the sheriff won’t find them,” he says.

“It’s a shameful thing.”

Iowa farmers still face a long fight, according to Dan Levitas, research director for Prairiefire, a farm advocacy group. “Anyone who thinks real agricultural reform is going to take place before 1988 and a change in this administration is not being realistic. We can do some things to hold back the flood gates, but we are facing a couple more years of intense struggle and farmers need to prepare for that,” Levitas said.

“It saddens me to see hopelessness and despair as a conditioned response from farmers rather than outrage and action. It also makes me sad because we tend to blame the victims of this crisis instead of looking at external causes.”

by Sherry Ricchiardi

At the age of nine, Maxine Bollin knows that the word “eviction” means she might have to pack her Barbie dolls and move out of the farmhouse she’s lived in most of her childhood.

Maxine’s parents, Kathy and Mike Bollin, have taken their legal battle to save the 80-acre farm near Keokuk to the Iowa Supreme Court.

“We’re still in limbo. Every day, we wait for the sheriff to serve eviction papers. It’s very stressful,” said Kathy Bollin, who work as a respiratory therapy technician to help pay the bills.

The Bollins’ fight hinges on two issues: whether they have a right to a one-year redemption period following the Federal Land Bank’s foreclosure on their farm and whether they should have first preference in renting that land during the one-year period.

“Some days we feel we’re going absolutely crazy; some days we shrug it off. We’ve been living out of cardboard boxes since the eviction notice was served on May 1,” Kathy said. “I get real scared that everything is going to break up. The only thing that really matters is staying together and raising these kids. There’s still a good, strong feeling between Mike and me despite all the pain we’ve been through.”

The Bollins have four children, ages 8 through 11.

By Sherry Ricchiardi

For the first time in 22 years, Kathy Langner of Dickens has taken a job off the farm. As a VISTA worker, she brings home $370 a month. The cash helps pay for heating and electricity, but it doesn’t help the depression that often sends tears flowing down her cheeks.

Kathy would rather be at her husband’s side in the fields.

“Marlin and I used to buy groceries, chase pigs and plant corn together all in one day. Now, I don’t see him until we sit down at the supper table. That’s a complete change for us,” Kathy Langner said.

For two years, the Langners have been on the verge of losing their land, a legacy they hoped to pass to their three sons. The once-bustling hog house, now empty, and the vacant cattle barn are evidence of their financial decline.

At first, Marlin Langner took to lying listlessly on the couch all day and leaving chores undone. His ulcers flared he swallowed tranquilizers to help him sleep at night.

“Our dad is such a proud man. He’s worked so hard. He didn’t deserve this,” said Keith, who at 17 is the youngest of the Langner sons.

Mental health worker Joan Blundall of Spencer says that farm families like the make up the bulk of her caseload these days. “These families are being forced to make choices they never dreamed they’d have to make. They don’t want pity. They want people to understand the complexities of the issues they face,” Blundall said.

“I’m worried about rural children growing up without dreams.”

For the Langners, the future is a question mark.

“It looks like we’ll be farming next year, but 1988 could spell trouble. We might not (have) cash flow,” Marlin Langner said. “We try to live a day at a time, but the creditors always are looking years ahead.”

Kirsten Hagedorn remembers the November day in 1984 when her father gathered the family together and related the news: He was in deep financial trouble and stood to lose the farmstead near Royal that his parents had passed on to him.

“It was the first time I’d ever seen dad cry,” Kisten recalled.

On Labor Day weekend this year, the family loaded their belongings into pickup trucks supplied by neighbors and friends.

Their destination: a new home – and new life – in nearby Spencer.

Today Dean Hagedorn is selling insurance.

His wife works for the Clay County Department of Human Services, a job she held for the past seven years.

“It’s over; I just have to live with that,” Dean Hagedorn said. This year he would have marked his 20th anniversary in farming.

By Sherry Ricchiardi

Phil Fetter insisted that “come what may” he was one farmer who would maintain his sense of humor. He couldn’t have known, when he made that statement in 1974 in an interview with The Des Moines Register, the troubles ahead.

Less than nine years later, the Chelsea farmer and father of 10 children went to a machine shed on his farm and put the barrel of a shotgun against his chest. On pieces of cardboard he scribbled, “I’m sorry. It’s best for everybody. The banker hates me. My family hates me.” He wrote “I’m sorry” on the knees of his blue jeans.

His 6-year-old son, Joe, happened onto the scene when he was looking for a fishing partner that hot July morning. Moments later, Norma Jean Fetter was standing at her husband’s side, begging him to move the gun away from his chest.

“He got angry at us and said, ‘Why are you doing this to me? Go away and leave me alone.’ His brother arrived and a neighbor came in. I had my hand on Phil’s shoulder when he pulled the trigger,” Norma Fetter said, as tears rolled from her eyes.

“Phil Fetter was conservative when it came to borrowing money and he had an excellent credit rating, his wife said. He was visible in the community; the kind of person others came to for moral support. But, in 1982, a series of events – low hog prices, high interest rates and a run of bad weather – eroded his financial base.

“He loved to be with the guys but all of a sudden, he was so ashamed,” his wife said.

“Toward the end, he actually was worried about putting food on the table. He waited for the eviction notice and talked to us ending up on the street. … He paced the floor, moped and cried with the kids.

“Phil truly saw himself as a steward of the land.

“His feelings went far deeper than anyone realized.”

By Sherry Ricchiardi

Larry Sharer knows first-hand what it’s like to fall victim to the farm crisis. Maybe that’s why the Dows auctioneer makes an effort to befriend farmers before bringing the gravel down on their belongings.”

“I don’t want to be looked at as an undertaker. People worth their salt in this business are sympathetic and respectful to these families,” Sharer said. “I have a sensitivity toward people facing this trauma. I’ve been there myself.”

The lumber and hardware business Sharer owned in Dows closed in 1985 as the economic crisis spread from the farm to the town, he said.

by Sherry Ricchiardi

Interview with Father Frank Cordaro conducted around the time the original story was published.

FATHER FRANK CORDARO:

Well, the crosses on the courthouse lawn, began when I first came here in October. I did some research and figured out how many sheriff sales there were here in Harrison County sinceRonald Reagen became president. And discovered there were 75 sheriff sales. Compared to,you know, a similar expansion of years prior to Ronald Reagan, were twelve. These salesamount to homes, business' and farms and vacant lots in the different communities. But they'reindicative of the larger crisis, that our state's been under since the beginning of the eighties.And the truth of the matter is, most people don't end up at a sheriff’s sale. That’s just the tip of the iceberg. The vast amount of people in rural agriculture get liquidated voluntarily. They have to make choices, reasonable choices, to get out or they lose their shirt, or go bankrupt and lose everything. So, most people leave voluntarily, involuntarily of course. So we started doing the planting of the crosses in the lawn at a prayer service a half hour before the sale. And it became kind of, you know, something the community would recognize as you know, there's another sale going on. A reminder. In my mind it's a liturgical function, to bring people in touch with the pain, and...and the agony, and put the sign of Christ there.

What happened then over the long haul, is I got tired of putting in crosses. It became veryclear poignantly clear, most people don't want to see what’s going on out here. In fact, at many of these sheriff’s sales the people who are being sold out don’t even show up. It often became me, the sheriff, a couple people from my parish and the creditors.

I’ve come to the conclusion that we know there’s a crucifixion going on out here, and we can show you all the white crosses with all the statistics. But what we haven’t been able to do is raise up the body of the people who are suffering. So that people can see the human suffering. And until we do that, I just don’t believe we will take ourselves seriously, or anyone else can do anything about the problem. I’ve been doing this thing on the courthouse lawn now for about two years. And it’s one of the more important pastoral things I think I do for the community.

DAVID PETERSON:

Can you tell me a little bit more about the day you were arrested with the farm family? What was the man’s name?

FATHER FRANK CORDARO:

Mark Vogal was the boy who was being evicted. His dad was John Vogal, a well-known farmer and activist in the area. John has some strong ideas. He thinks that the reserve bank is unconstitutional. Well, I don’t know if it’s unconstitutional or not. I know the banking system in this country is unjust, and part of the evil system we have to deal with. Whether it’s lawful or not hasn’t got anything … it at least doesn’t have a lot to do with me. But what John was experiencing was the loss of his farm, and his livelihood. And his son was on one of the farms and they were being evicted. And he called me and asked me if I would help him protest it in a nonviolent way. So we orchestrated and organized a witne3ss on the day of the eviction. We made an agreement with the sheriff that two of us would be arrested, and that we were doing this out of conscience and trying to raise the larger issue. We offered them no resistance other than our bodies, and we pushed it to the point of arrest.

On the day of the sale, well, the night before the sale, I spent the better part of the night helping the Vogals move out of their house with their friends. Made sure that everything was out, away from the property. And then on the morning we had a catholic mass. The Vogals are Catholic. And the sheriff came out. We had a couple of speeches. There weren’t a lot of us. Most of them were scared to show up. And then when the time came, everyone cleared the property except Mark Vogal and I, and we were arrested by the sheriff’s department, and taken to the court and charged.

One of the things that the Harlen protest really clearly showed by the negative reactions, the strong, strong reaction to that protest, was that we are seriously in the deep grip of denial here in our community. We know there’s a crisis. And everywhere tells us that in our head. People don’t want to deal with the substance of the issue. And it showed itself, manifested itself in two distinct ways in the Harlan effort.

The people who were against the Lickties [another family] kept saying, “They’re a bad example.” Well, you know, there aren’t any good examples out here. And that, “They’re the wrong people.” And they found a hundred and one things wrong with the Lickties. To say, “that’s why they deserve what they’re getting.” Those are people who normally, usually aren’t hurting. And I’ve discovered that it's far easier to blame individuals, for failure, than to take on the structural things that need to be changed. So when a person can blame the other guy, then they aren’t responsible, or obligated to do anything to change the situation.

Now we know it’s larger than one person. The towns are disappearing, the businesses are disappearing, the churches are dwindling, the school populations are being eradiated, liquidated, yet continually, and especially those who choose to stand up and say, “we want to fight”, their neighbors commit character assassination on them. Now if the Lickties had fallen away in a quiet manner like most people, no one would have given a darn one way or another about them. But the fact that they said, “Father help us fight this. It’s bigger than us.” The fact that they wanted to bring to light what everyone would prefer to keep in the dark, that was very clear to me that we are in the grip of denial.

The other side of the coin is there are people out there who are close to the Lickties, financially in the same situation. When asked, “why don’t you come to the demonstration?” They said, “we know you’re right Father. But I gotta go to the banker next month, I gotta go to a lender. And if they see my face on TV they’ll see me as a hard person to deal with, and I may not get my money. I can’t afford to show my face in public. But I know there’s something wrong.” It's another case of denial.

The shame, the real tragedy of it is that I’m living here with some of the best people America has to offer as far as their concern, their sympathy, their community spirit. Rural people are far more sensitive to each other than I believe city folks are. But when it comes to this kind of economic situation, they’re as cold as ice. And they’ll just see their neighbor, you know, and watch them go under and won’t say a darn thing. If the neighbor should want to fight, everyone will find something wrong with him. And that’s the ethic that I think we’ve got to really address. Especially those of us in the church. And those of us who want to turn this thing around. Because if we don’t get underneath the ethic, we’re not really going to get to the real substance o the problems.

DAVID PETERSON:

Could you tell me a little bit about the role the church has played? What it’s continuing to play, and what you think of it?

FATHER FRANK CORDARO:

Well, I don’t think it’s played a very strong role. At least not as strong as it should be. Often times, the professional people who are working in the church with the rural struggle, quickly gravitate to being effective, and embrace, you know, a very concrete legislative agenda. This needs to be done. I’m not taking that away. But we’ve really advocated, really taken it to our communities and confronted them with the greed ethic and set this whole thing up.

Now our bishops and church leadership have come up with some great statements about the evil of the system. Yet, middle management, that is to say, those of us who are pastors in churches, we’re afraid to speak from the pulpit. And worse yet, we’re afraid to show up in public and identify with those who are hurting.

These orchestrated demonstrations are simple efforts to try to bring to light again what people like to keep hidden. I often get complaints like, “by the time they come to the sale it’s late.” Well, if for no other reason we’re developing a liturgy, a funeral of sorts, so people can have a catharsis about what’s happening to rural America. How often when I stand with people, in those moments, they appreciate that someone was there, just to share in their pain. And someone to get up and say, “this is wrong,” and try to … whoever would listen. Many of the families that choose to fight in this manner, come out of the whole episode in a much healthier, spiritual state. Those who disappear at night, they’re scars that will stay for years.

DAVID PETERSON:

What do you think about farm retreats? Do you think they help?

FATHER FRANK CORDARO:

Alright, I think that sort of ministry, being with them, showing support, and just you know, a presence saying, “God is with you”, is very important. Yet, I still believe another aspect of the gospel is struggling with it, screaming with it, standing in front of the system saying, “STOP!” If that component is not part of our gospel ministry, we’re just standing at the graveside, saying prayers to people as we bury them. And there’s got to be something redemptive in this thing. And part of the redemption is the struggle, and we have yet to really come to grips with what it means to struggle. Again, we’re going against all the odds because no one wants us to struggle. The folks themselves don’t want to face up to what’s happening. And that needs to be confronted. I believe the church is the only voice that can do that.

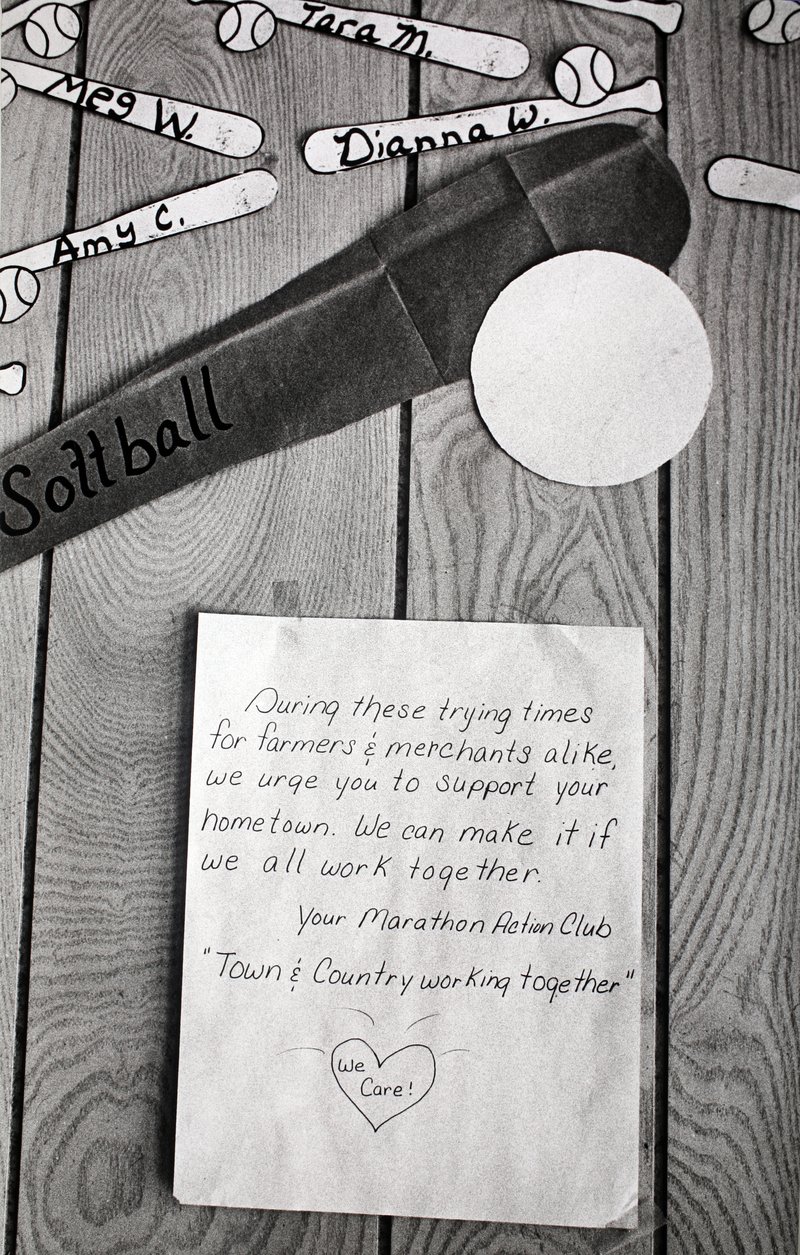

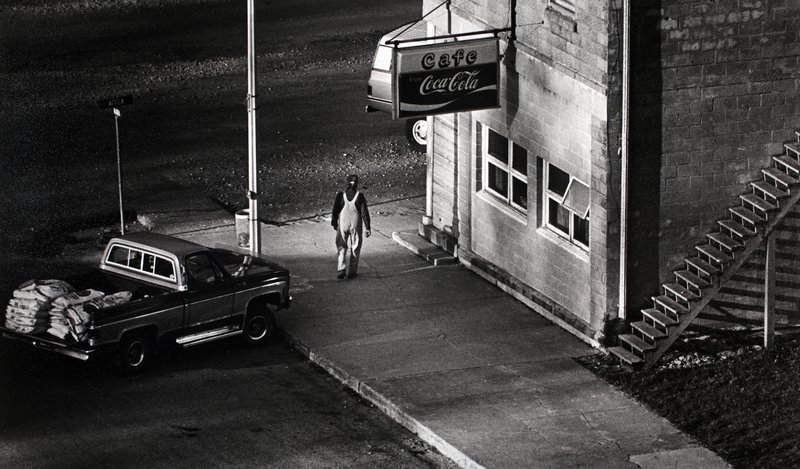

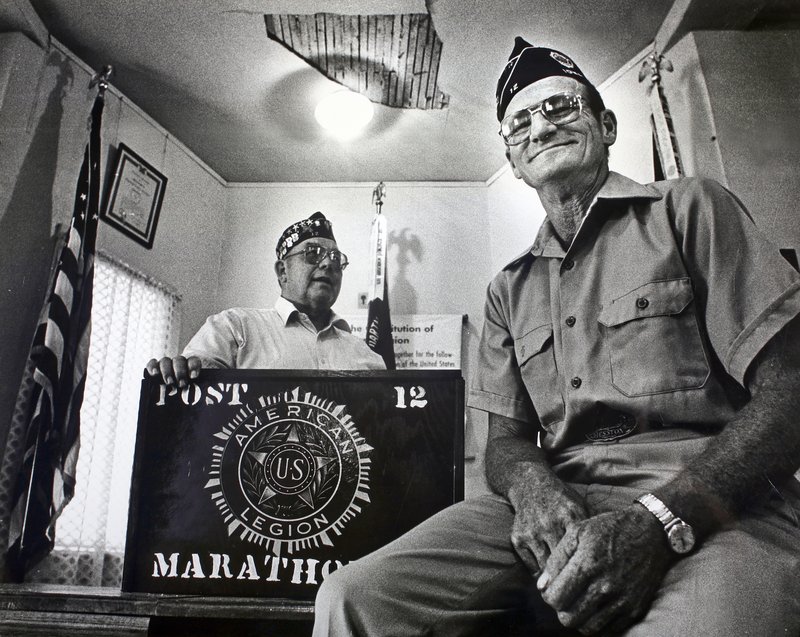

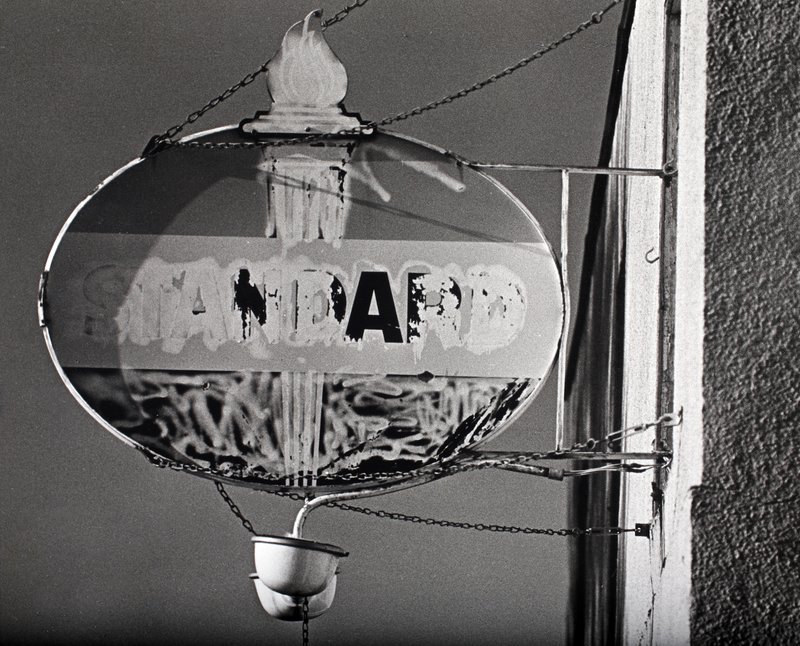

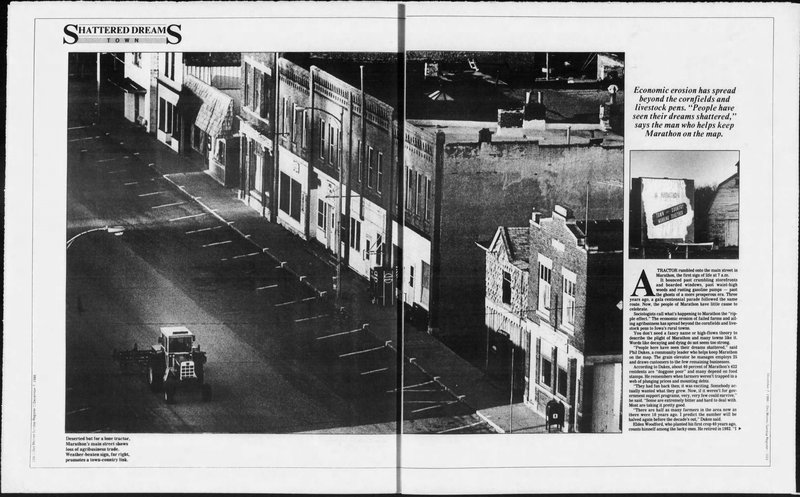

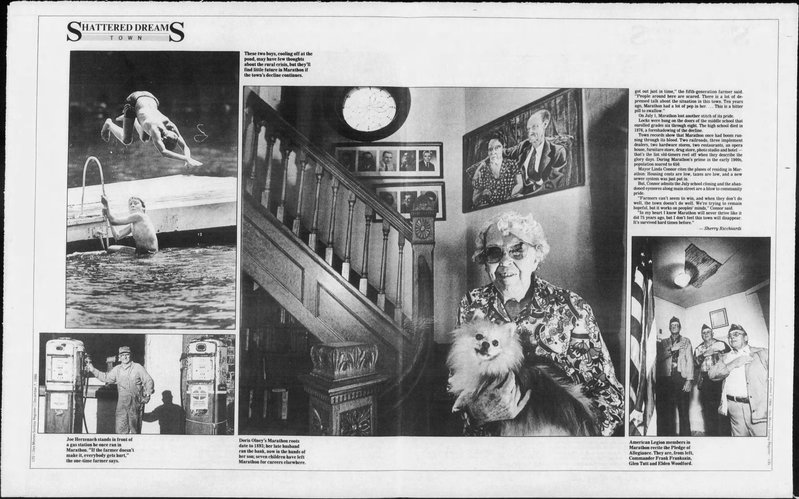

The End of the Run for Marathon, Iowa

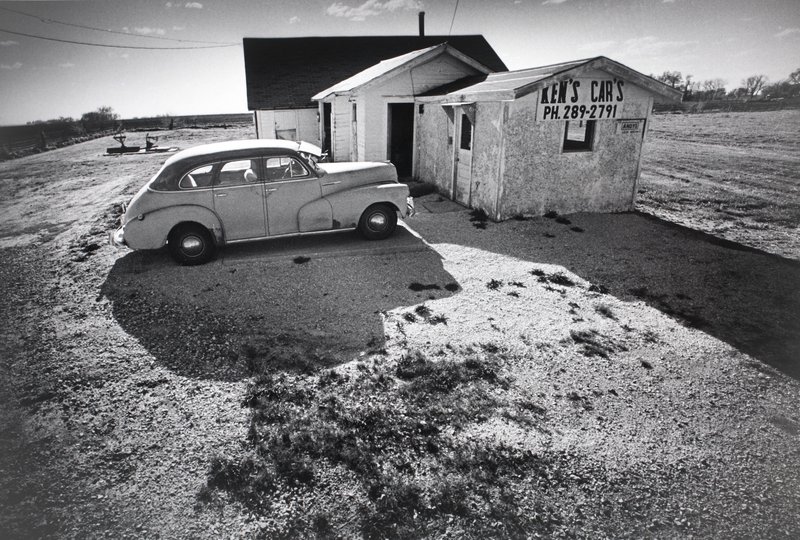

Economic erosion spread beyond the cornfields and livestock pens. “People have seen their dreams shattered,” says the man who helps keep Marathon on the map.

A tractor rumbles onto the main street in Marathon, the first sing of life at 7 a.m.

It bounced past crumbling storefronts and boarded windows, past waist-high weeds and rusting gasoline pumps – past the ghosts of a more prosperous era. Three years ago, a gala centennial parade followed the same route. Now, the people of Marathon have little cause to celebrate.

Sociologists call what’s happening to Marathon the “ripple effect.” The economic erosion of failed farms and ailing agribusiness has spread beyond the cornfields and livestock pens to Iowa’s rural towns.

You don’t need a fancy name or high-flown theory to describe the plight of Marathon and many towns like it. Words like decaying and dying do not seem too strong.

“People here have seen their dreams shattered,” said Phil Dukes, a community leader who helps keep Marathon on the map. The grain elevator he manages employs 25 and draws customers to the few remaining businesses.

According to Dukes, about 40 percent of Marathon’s 422 residents are “doggone poor” and many depend on food stamps. He remembers when farmers weren’t trapped in a web of plunging prices and mounting debts.

“They had fund back then; it was exciting. Somebody actually wanted what they grew. Now, if it weren’t for government support programs, very, very, few could survive,” he said. “Some are extremely bitter and hard to deal with. Most are taking it pretty good.

“There are half as many farmers in the area now as there were 10 years ago. I predict the number will be halved again before the decade’s out,” Dukes said.

Elden Woodford, who planted his first crop 40 years ago, counts himself among the lucky ones. He retired in 1982. “I got out just in time,” the fifth-generation farmer said. “People around here are scared. There is a lot of depressing talk about the situation in this town. Ten years ago, Marathon had a lot of pep in her. … This is a bitter pill to swallow.”

On July 1, Marathon lost another stitch of its pride.

Locks were hung on the doors of the middle school that enrolled grades six through eight. The high school died in 1976, a foreshadowing of the decline.

Town records show that Marathon once had boom running through its blood. Two railroads, three implement dealers, two hardware stores, two restaurants, an opera house, furniture store, drug store, photo studio and hotel – that’s the list old-timers reel off when they describe the glory days. During Marathon’s prime in the early 1990s, populations soared to 650.

Mayor Linda Connor cites the pluses of residing in Marathon: Housing costs are low, and a new sewer system was just put in. But, Connor admits the July school closing and the abandoned eyesores along main street are a blow to community pride.

“Farmers can’t seem to win, and when they don’t do well, the town doesn’t do well. We’re trying to remain hopeful, but it works on peoples’ minds,” Connor said.

“In my heart I know Marathon will never thrive like it did 75 years ago, but I don’t feel this town will disappear. It’s survived hard times before.”

bu Sherry Ricchiardi

One Family's Story

Elmer Steffes sat alone at the kitchen table, a rifle clutched in his thick farmer’s hands. His wife was working the graveyard shift at the nearby nursing home. She wasn’t due back until dawn.

“When I returned, the doors were locked,” Pat Steffes recalled. “That wasn’t like Elmer.”

Maybe her frantic pleas and loud pounding jolted him back to reality. Or perhaps it was her gentle understanding of his grieving that led him to put the gun aside.

Losing a farm was like wiping out a life, he had told her. The incident occurred as the foreclosure date on their farm approached.

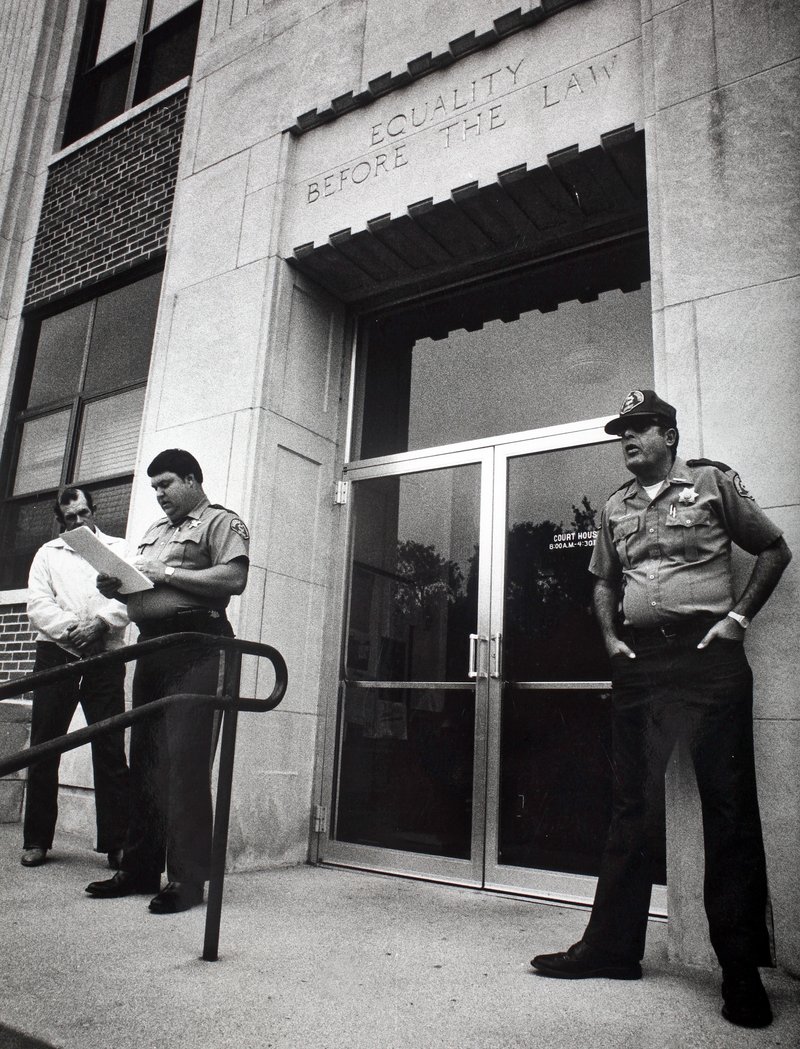

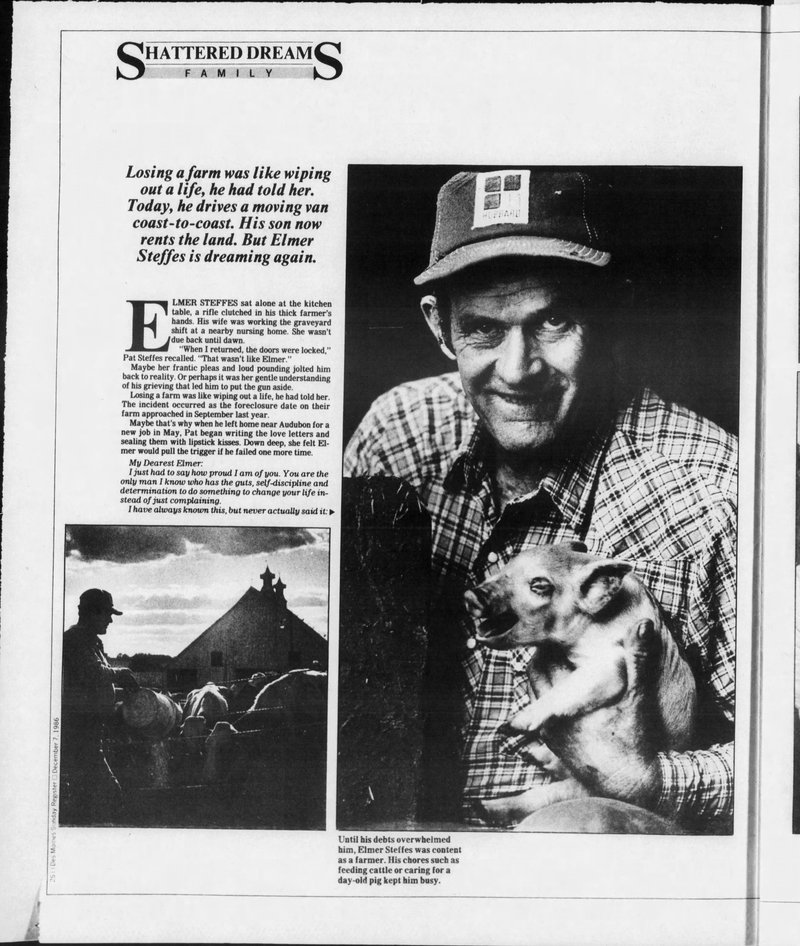

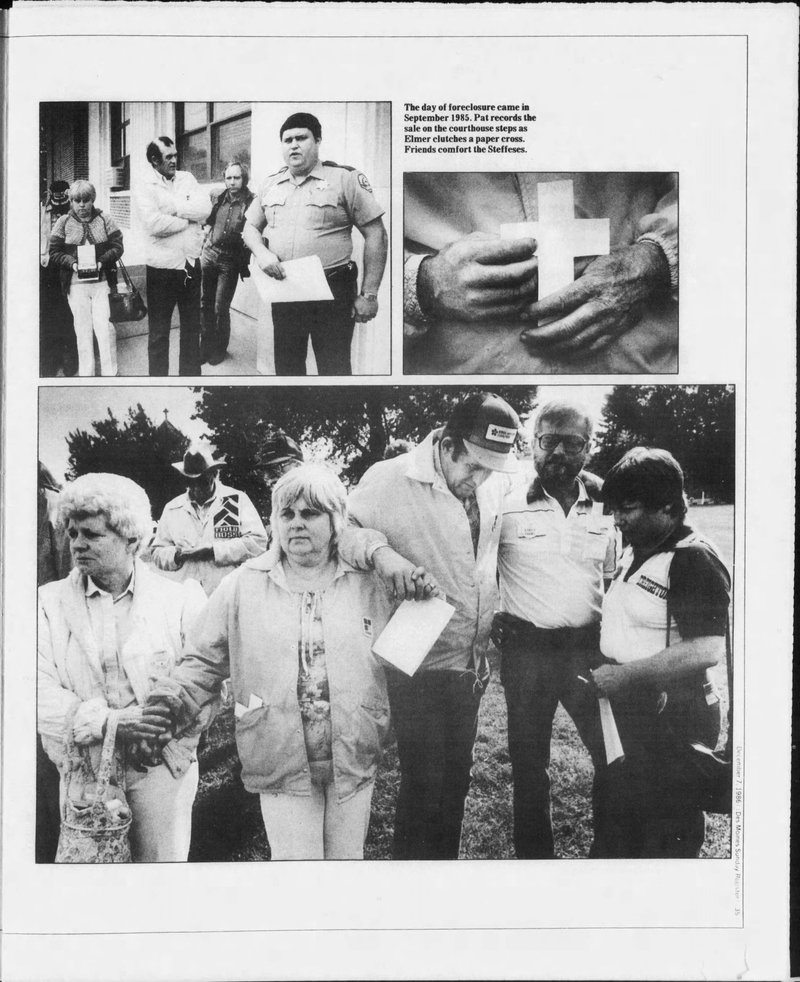

The day of foreclosure came in September 1985. Pat records the sale on the courthouse steps as Elmer clutches a paper cross. Friends comfort the Steffeses.

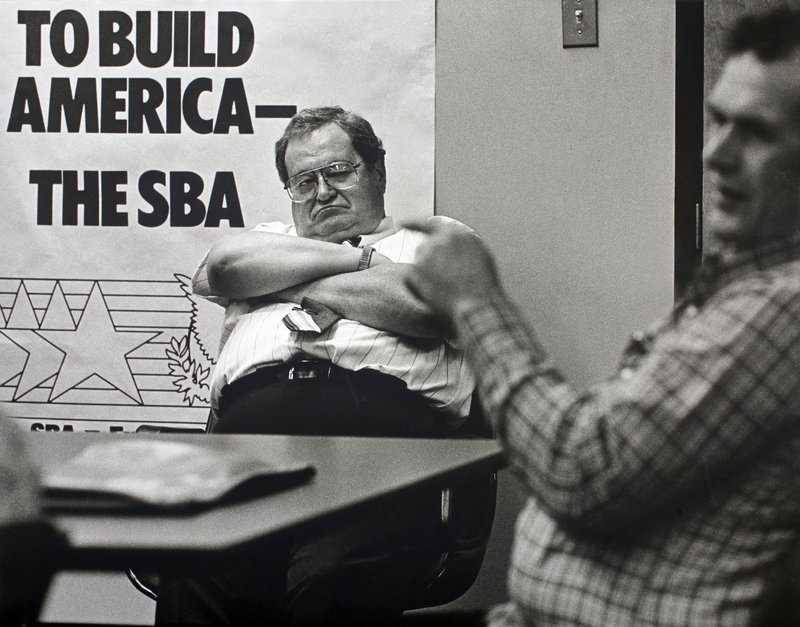

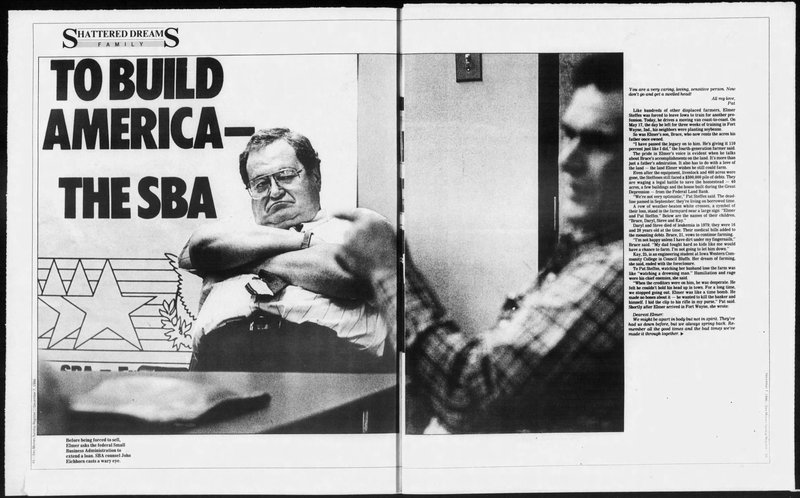

Before being forced to sell, Elmer asks the federal Small Business Administration to extend a loan. SBA counsel John Eichhorn casts a wary eye.

Maybe that’s why when he left home near Audubon for a new job in May, Pat began writing the love letters and sealing them with lipstick kisses. Down deep, she felt Elmer would pull the trigger if he failed one more time.

My Dearest Elmer:

I just had to say how proud of I am of you. You are the only man I know who has the guts, self-discipline and determination to do something to change your life instead of just complaining.

I have always known this ,but never actually said it: You are a very caring, loving, sensitive person. Now don’t go and get a swelled head! All my love, Pat

Until his debts overwhelmed him, Elmer Steffes was content as a farmer. His chores such as feeding cattle or caring for a day-old pig kept him busy.

Like hundreds of other displaced farmers, Elmer Steffes was forced to leave Iowa to train for another profession. Today, he drives a moving van coast-to-coast. On May 17, the day he left for three weeks of training in Fort Wayne, Ind., his neighbors were planting soybeans.

So was Elmer’s son, Bruce, who now rents the acres his father once owned.

“I have passed the legacy on to him. He’s giving it 110 percent just like I did,” the fourth-generation farmer said.

The pride in Elmer’s voice is evident when he talks about Bruce’s accomplishments on the land. It’s more than just a father’s admiration. It also has to do with a love of the land – the land Elmer wishes he still could farm.

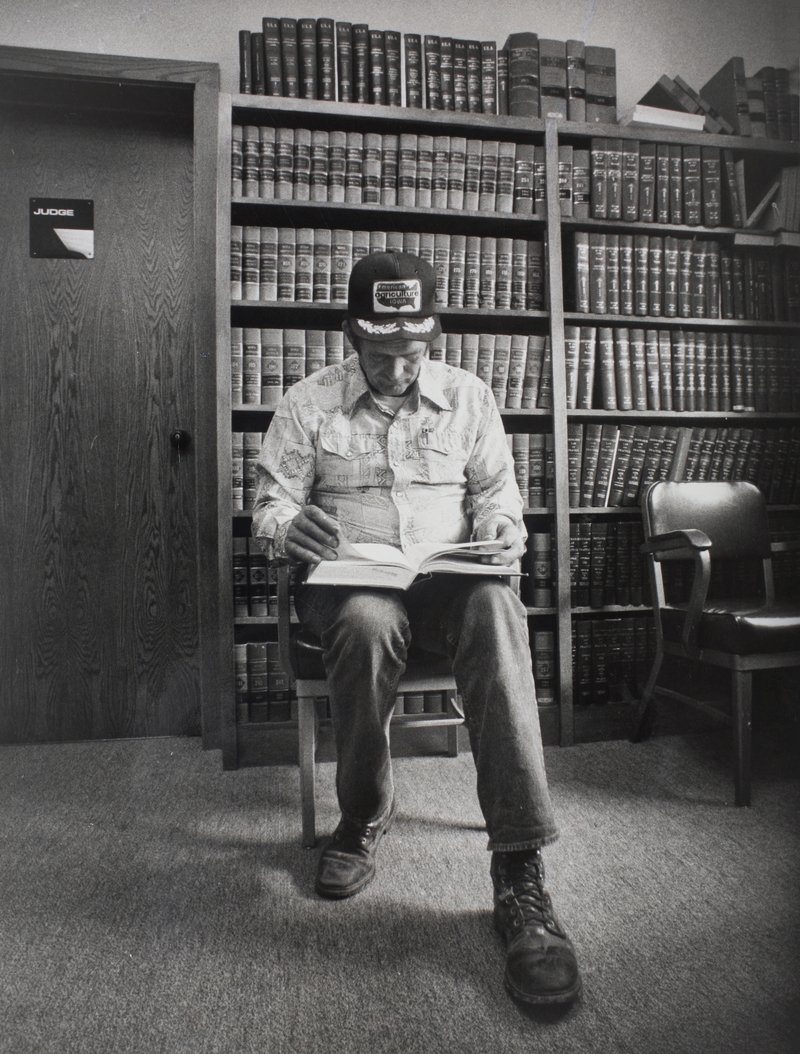

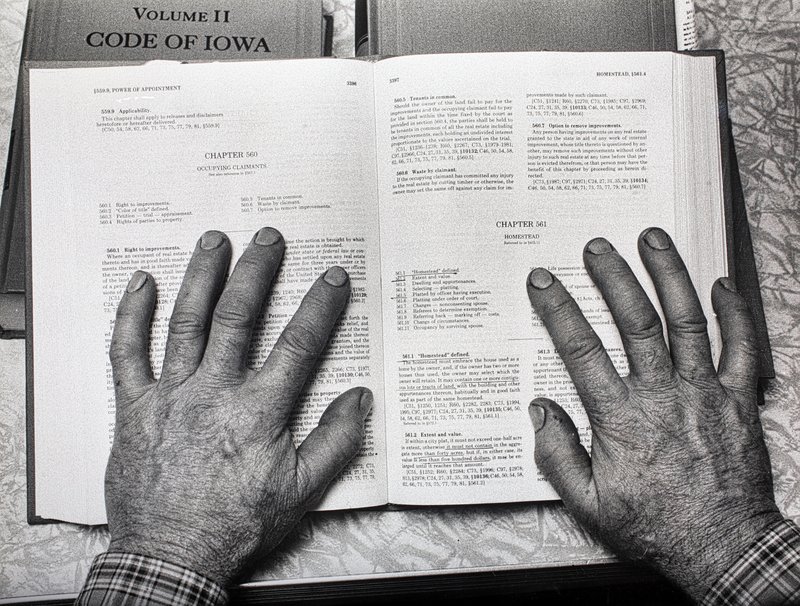

Even after the equipment, livestock and 460 acres were gone, the Steffes still faced a $300,000 pile of debts. They are waging a legal battle to save the homestead – 40 acres, a few buildings and the house built during the Great Depression – from the Federal Land Bank.

“We’re not very optimistic,” Pat Steffes said. The deadline passed in September, they’re living on borrowed time.

A row of weather-beaten white crosses, a symbol of their loss, stand in the farmyard near a large sign: “Elmer and Pat Steffes.” Below are the names of their children, “Bruce, Daryl, Steve and Kay.”

Daryl and Steve died of leukemia in 1979; they were 16 and 20 years old at the time. Their medical bills added to the mounting debts. Bruce, 21, vows to continue farming.

“I’m not happy unless I have dirt under my fingernails,” Bruce said. “My dad fought hard so kids like me would have a chance to farm. I’m not going to let him down.”

Kay, 25, is an engineering student at Iowa Western Community College in Council Bluffs. Her dream of farming, she said, ended with the foreclosure.

To Pat Steffes, watching her husband lose the farm was like “watching a drowning man.” Humiliation and rage were his chief enemies, she said.

“When the creditors were on him, he was desperate. He felt he couldn’t hold his head up in town. For a long time, we stopped going out. Elmer was like a time bomb. He made no bones about it – he wanted to kill the banker and himself. I hid the clip to his rifle in my purse,” Pat said.

Shortly after Elmer arrived in Fort Wayne, she wrote:

Dearest Elmer:

We might be apart in body but not in spirit. They’ve had us down before, but we always spring back. Remember all the good times and the bad times we’ve made it through together. The weather straightened out and Bruce is in the fields today … Take care of yourself and stay positive

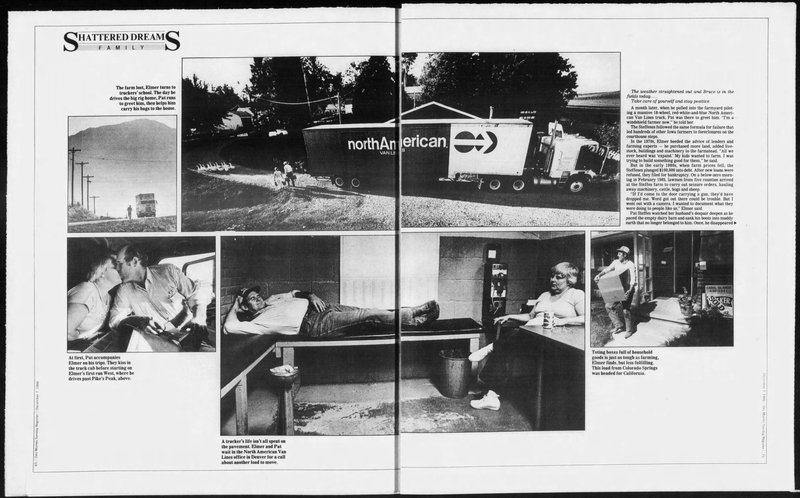

A month later, when he pulled into the farmyard piloting a massive 18-wheel, red-white-and-blue North American Van Lines truck. Pat was there to greet him. “I’m a windshield farmer now,” he told her.

The Steffeses followed the same formula for failure that led hundreds of other Iowa farmers to foreclosures on the courthouse steps.

In the 1970s, Elmer heeded the advice of lenders and farming experts – he purchased more land, added livestock, buildings and machinery to the farmstead. “All we ever heard was ‘expand.’ My kids wanted to farm. I was trying the build something good for them,” he said.

But in the early 1980s, when farm prices fell, the Steffeses plunged $100,000 into debt. After new loans were refused, they filed for bankruptcy. On a below-zero morning in February 1985, lawmen from five counties arrived at the Steffes farm to carry out seizure orders, hauling away machinery, cattle, hogs and sheep.

“If I’d come to the door carrying a gun, they’d have dropped me. Word got out there could be trouble. But I went out with a camera. I want to document what they were doing to people around us,” Elmer said.

Pat Steffes watched her husband’s despair deepen as he paced the dairy barn and sank his boots into muddy earth no longer belonging to him. Once, he disappeared for three days, another time, she found him in a machine shed stringing a rope from the rafters.

“I called the county health nurse and she came right out. We coaxed Elmer into the house and tried to convince him that he had reasons to live,” Pat Steffes said. The weekend before the foreclosure, Elmer was hospitalized for high blood pressure and a possible heart attack.

When he passed the test at truck driving school during the summer, Pat sent the follow message:

Dearest Elmer:

I am so grateful the Lord has given you a second chance. I feel good that you are positive, growing and learning again. I hope with this change we can forget the terrible, horrible pain of the past.

“The thing I feel worst about is how much time we wasted venting our frustration and pain on each other … I’ll try never to be a nag again.

Elmer Steffes settled his hefty frame into a booth at the truck stop somewhere past Denver, Colo., and ordered his favorite – a hot roast beef sandwich on white bread. For a few moments, he relived the year of disgrace. “Losing a farm is a grieving process. It’s a wearing down that gets to the heart of your brain. After five years of suffering, I needed time to repair myself. I was scare to dream,” Elmer Steffes said.

He credits his wife, a few close friends, and a psychologist who stood at his side the day of the foreclosure with reviving his will to live.

In November, the odometer in his truck hit the 45,000-mile mark. He has delivered a $25,000 piano to a Florida millionaire and unloaded furniture on New York’s Broadway. He’s eaten grits in Alabama and fresh crab on the Mississippi Gulf.

“Not bad for a country boy,” he jokes. But there have been a few hard knocks since that country boy left the quiet of his Audubon Country farm.

Recently, a drifter he hired to help unload the van robbed him of $120. “You can’t keep your guard up high enough out here,” Elmer said. The trucks stops are “floating with drugs – white powder, pills, needles. I’ve seen it all, but I don’t feel good talking about it.”

For a few weeks, his wife traveled with him, sharing the dingy motel rooms and greasy-spoon dinners. She’s back home now, writing a book about their life.

Elmer phones his son regularly for farming reports and sends cash to help wih the debts whenever he can. “When I go home and see the livestock Bruce is raising, I feel proud. He even got a field of beans in early. He’s all business when I call, just like his old man.”

Elmer Steffes, at the age of 50, is dreaming again.

“The truth is, I would like to farm again someday, but this time I plan to start small without borrowing a single cent. I’d like to raise a few livestock and plant a few acres just to get my hands back in the dirt. That’s my biggest dream,” he said.

by Sherry Ricchiardi

Interview with Elmer and Pat Steffes conducted around the time the story was originally published.

DAVID PETERSON:

Elmer could you talk a little bit about how you felt that day when you lost your farm?

ELMER STEFFES:

Well we lost. We were talking about foreclosure. Well first off the bank used the word“replevin”[1]. They didn't want to give us a day in court. They just thought they could runit through without any formalities, or just behind the doors. Well, we did get our day in the courtroom, and later that morning, why the bank’s lawyer says that, “Elmer you nolonger have any rights. At this point in the game you have no rights.” That bothered mequite a bit. You know, being of the United States and then they take all your rights away...and after that they continue to walk over me just like I didn't have no rights. Thatbothered me quite a bit. You know, being of the United States and then they take all yourrights away...and after that they continue to walk over me just like I didn't have no rights.They made the rules up as they went along. Uh...I was wore (worn) down pretty sicknervous/ My system was just tired out, just burned out. Well then when they come to replevin the stuff, they come with lots of power. Just like I was a real criminal. The federal investigator was along. Th criminal investigator was also along. They keptthings moving. The kept … so you didn't have time to think. And looking back, why, it was a pretty big show.

We went down to S.B.A.[bank] to renegotiate the loan. Maybe make the payments a littlesmaller. Find out some workable solution that would be good for us both. After wetalked to them for about an hour it was just like talking to a fence post. That’s all I got to say.

INTERVIEWER:

Elmer at one time you contemplated taking your own life. Is that right?

ELMER STEFFES:

Yeah, that was in the summer time. Things were moving and they told me I was a failure. And I started to feel like a failure. I started to dwell on it, like I was a failure. And I just wanted to give up. Just get out of it. I hurt so bad inside that I … uh … I did. And then we went to this Sheriff’s sale, which was after the replevin. I started to get callous to it. I didn’t hurt quite as bas at the sheriff’s sale. But I knew there was an injustice being done. I knew they was bending the rules to make their own. Things weren’t right. They walked over me, just like I had no more rights. They just typed in what they want and crossed out what they want, and I knew this was wrong. In the meantime, we went to different meetings. You now, amongst farmers, and people that were seeing what was happening. So we could learn. We studied federal law a little bit, and that was too dep and that takes too long, and it takes too much money to fight it. So then we started studying Iowa law. Ande we got the Iowa code books. I'm very happy with what I learned, and they'll never take this away from me. And there's a lot of things in there just for the reading, that would help everybody know what your rights are. Andif you have something to back you up, then you're not ashamed to say what you mean or what's right and what's wrong.

DAVID PETERSON:

Let me go back to the farm sale again. One more time. Uh...can you remember anything you said to Pat, that day - what the two of you talked about? On that day?

ELMER STEFFES:

No, give me a hint.

INTERIVEWER:

Just at the time...did you express your feelings to each other. Ord' you pretty much...

ELMER STEFFES:

Not really. We each had a job to do.

PAT STEFFES:

I think we were both pretty drained at that time.

ELMER STEFFES:

It was...it was like defeat. You know, very much defeat. What you'dworked so hard for, many, many years, to get. How your partner, so called partner, in allthese business dealings he outmaneuvered you and he took the land away. They told us that

figures don't 1ie but liars do figure. And looking back now ... the liars are figuring.They figured out a way they could get this farm away from us in a very short period of time. That you didn't have time to get on the defense. They moved so fast. Every Fridaythey send out a letter. They work on it all week, Friday they send out a letter, so the lawyer would, so you'd have a shitty weekend, keep you mind bad, keep you mind so you couldn't get on the defense. You was scared all the time, I mean.

PAT STEFFES:

So it was about a month later when he started working for NorthAmerican (Van Lines).

ELMER STEFFES:

Early in the game the bank (loan officer) made the comment that he was gonna break myspirit. And he's gonna get me off the farm, and he's gonna do it in thirty days. Well, it tooka lot longer than that, but eventually he got my spirit broke. Eventually he had us out ofmoney, that I had to leave the farm and go find another job. I answered ads, and well thenI found a job with NorthAmerican Van Lines. The recruiter called and says if I wanted to come to school, and they said they move furniture. And I says, "No, I'd never movefurniture."

I said that all my life that I'd never want to move people's furniture.

After I went to school and learned how, well, … now I like to move furniture because

I'm in contact with a lot of people. Each job is different. You learn a lot from each job, and it gets done. Survival. There's a lot of challenges out there. Each job is a challenge.

DAVID PETERSON:

We'll let Pat go on now.

PAT STEFFES:

Okay, you want me to talk about foreclosure first?

DAVID PETERSON:

Yeah...why don't you talk about foreclosure a little bit. That day... and...

PAT STEFFES:

I guess at that point, I felt very drained as though, you know... you'd fought as long andhard as you could to keep everything and yet... it was still just kinda disappearing right infront of your eyes. I guess my main concern was just to keep our family going. To keep everybody alive, and... uh, functioning. And to continue to struggle. To save what wecould from the farm.

OK now what? More on the foreclosure?

DAVID PETERSON:

Yeah a little about that if you want to talk about that. Then we’ll go on to the letters you wrote, and all that too.

PAT STEFFES:

Okay, well, like I said...you know.

We were all very depressed and felt a sense of great loss. And like Elmer said, defeat.The day of the foreclosure, you were so drained of energy, you’re just doing good to put one foot in front of the other. It just tears you up so bad inside that you worked so hard, so many years and everything is being taken away from you in just a few minutes on thecourthouse steps. The people that don't really care what happens to you .

When Elmer started looking for jobs there were a lot of times he really didn't have the energy it required to put himself into a job. When NorthAmerican Van Lines did call, and he was interested, it was a real sense of relief to me that he had regained enough self esteem, and enough energy, to want and go out and work. And on top of that, we were so broke that we, he had to do something. That was one of the things I had said. And you know, well, he asked me how I felt about him going away like that.And I says, "Well, at this point, I can't be too picky. It's a job. It'll bring in money. Maybehelp to get us started again." And so he went to Fort Wane to school for three weeks. I knew this was a real tough period for him to leave the farm. There was a lot of mixed feelings.

You know, he was a little excited about the job. But he was hurting a whole lot over thefact that he was leaving the farm and his home and his family.

So I started writing love letters every day. I wrote them first of all for moral support, so hecould get through the three weeks of schooling, hich wasn't easy. And to kinda help, to let him know that if we weren't together we still could perform as a team, or as a couple,or as a family.

Second of all I wrote to him, because most truck drivers after they get on the road, theythey have a special girl somewhere. And I thought I

might as well be that special girl as somebody else... (pause)

The third reason -- for a long period of time, when he was real depressed our line of communication wasn't that great. And I didn't want that line of communication brokendown again. I wanted to keep that going. So that was another reason I wrote to him.

DAVID PETERSON:

What'd you feel like the day he drove the truck home?

PAT STEFFES:

I was excited.

The day he brought the truck home from Fort Wayne he was a little late getting in. So theanticipation, and seeing the new truck, and seeing him after I hadn't seen him for almost a month, was pretty great. And so I was real excited. He started out

with a class of hundred in his class. And by the time they got their trucks they were down to about thirty drivers. So, I felt like, if he had the determination, and everything ittook to make it through school and be ready to go on the road, to get the truck, and to goon the road. I was real happy for him. As it worked out, the first trip I got to go withhim. It was a short trip, but...I had a few days off from work it worked out. I just hopped in the truck and went along.

DAVID PETERSON:

Where’d you go?

PAT STEFFES:

We went to Rapid City, South Dakota. And we were gone... We left on Wednesday night and we were back on Saturday afternoon.

DAVID PETERSON:

What about your trip out West? That was the second time, wasn't it?

PAT STEFFES:

Yeah, that was the second time I went with him. Well, I just don’t know what to say. (laugh) I guess I wanted to be with him. I wanted it to be a family project. I didn't wanthim to be running out there, thinking he was by himself, and me here at home all by myself. I wanted to keep us going as a, as a family unit. And, I enjoy traveling. Most of the time we enjoy being together. So I was real excited that I could go along for a while, to Denver and Colorado Springs, see Pikes Peak. I enjoy helping with the moving process. Meeting the people.

DAVID PETERSON:

You called home several times to Bruce (their son) when I was with you. You and (Elmer) both talked of Bruce. What are your hopes for Bruce?

PAT STEFFES:

Bruce wants to farm, really, really bad. And I think one of our biggest hopes at this pointis that somehow or other he can stay here and farm this farm. It's taken a lot of sacrifices for everybody, and even for Bruce because he doesn’t go out a lot. A lot of times he's real saving with his money. But I think that's his biggest goal, if he could , continue to farm.

DAVID PETERSON:

What are your hopes and dreams £or yourself?

PAT STEFFES:

Well, just to get some of our financial problems resolved and to get back stable financially. Be able to spend some more time together than we are right now. Hopefullyhe keeps his job (at NorthAmerican Van Lines) and keeps the truck going. There’s a good chance that we’re going to be able to save part of our homestead. And then to keep the truck on the road and to spend some time with him on the road. I like to travel. I like to meet people. We like to be together some of the time.

ELMER STEFFES: I

guess my dreams for the future right now are to run the truck for a few more years. My hobby is still the farm. And to send money home so Bruce can get started farming again. And my biggest dream would be getting back into livestock. Probably the happiest time are when I come home for just a short time, and (Bruce) has a job for me, like letting me plow my favorite field and work with the soil and check the new-born animals. I still … when I’m on the road I farm every day from behind the windshield.

[1]

Replevin An action seeking return of personal property wrongfully taken or held by the defendant. Rules on replevin actions vary by jurisdiction. For example, a bank might file a replevin action against a borrower to repossess the borrower's car after he missed too many payments.

To license the images in these stories contact David Peterson here.

How this Photo Essay Came About

It’s early February, 1986.

Winters in Iowa are bleak and long … so it always seemed. The weather was matching my mood. I was driving through the state, mostly on blue highways, fulfilling assignments. This wasn’t unusual - we were a “state wide” newspaper, the newspaper that “Iowa depended on”. A slogan that I was often dubious of … and a notion that would soon be confirmed.

The farm crisis started in the late 70’s, and had now reached its apex. I had been involved in some of the stories, but always felt like an appendage to the written story, and a grip for reporters to drag along, drive the company car, and offer a picture or two to accompany 50 inches of copy. To make matters worse, newspapers were dropping into Iowa to do “farm crisis” stories, and running big spreads with both words and pictures … many lacking the depth to tell the whole story. I had a word for that - “parachute journalism”. These other reporters and photographers, despite their efforts, in my opinion had come up short.

As I was driving on that February day looking at farm houses and dying small towns, I realized how invisible this story was and the only way to tell it was to put a face on it. But that would require an investment of time.

I had come to a moral and professional crossroads. This crisis was quietly tearing my state apart - a state that was still defined by small family farms, and many agricultural businesses. So I had to ask myself the hard question. As a photojournalist, what was my responsibility?

With all of this weighing on me, I set a meeting with the managing editor to discuss a farm crisis project with emphasis on telling this story visually … through the eyes and hearts of the people most affected by it. I asked for two months away from other assignments to do it. His answer … "Dave, I think we’ve already done enough, and besides, the story is starting to wind down.” I wasn’t ready to give up. Time to pivot and throw the “Hail Mary”.

The previous year the National Press Photographers and Nikon Cameras had established a sabbatical which allowed a photojournalist to work on an extended project fitting the theme “The Changing Face of America”. It required that the recipient take a three-month leave of absence from their newspaper (unpaid) and also receive a $10,000 grant to fund the project. The inaugural winner was April Saul from the Philadelphia Enquirer who did a story on the assimilation of the Hmong population in Philadelphia. It was very well done and a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for Feature Photography that year. A tough act to follow. The deadline for entry proposals was coming up.

Believe me, I had no aspirations to win a Pulitzer - just to submit my proposal and hope that fate was on my side to do the story. The chairman of the selection committee was Tom Hardin, the director of photography at the Louisville Courier Journal. When I decided to leave the Topeka Capital-Journal, Tom's newspaper was the only other one that I was interested in besides the Des Moines Register, and I had spent a couple of days their on a “recruiting” visit ten years ago. So I knew Tom … not that I felt that that gave me an advantage in this situation.

So I entered the “contest” on a wing and a prayer and submitted my proposal. A few weeks passed, and I received a phone call from Tom. He said, “we need more specifics … give us a more detailed outline of your project and what you hope to accomplish.” He said that if I could do that convincingly, then the sabbatical was mine! So I followed up on his suggestion, and a week later he called me again and said “you got it”. I was thrilled, but also scared. Could I deliver the goods?

I worked out a plan with the Register to split the three months that I would be gone into three parts - one in the spring, one in the summer and one in the fall. That way, I could expand the time to include the planting/growing/harvest seasons, which would also hold some symbolism. It would also allow me to work on the project on my days off at the paper. The Register also agreed to let me use their film, and darkroom. A grand gesture, considering that they stiffed me on doing the project on their time and their dime. I swapped cars with my wife and drove her Ford Escort, which got better gas mileage than my Saab. She won on that exchange!

So I was on my way, all alone with a Ford Escort, my cameras, a slew of ideas and no guarantees! Daunting! As I started to accumulate photos, I thought it wise to include the newspaper as a possible avenue for publishing the story. After all, it WAS an Iowa story. Every few weeks I would meet with the managing editor (the same one who turned me down) and spread photos on the floor of his office. He viewed them quietly and after a few sessions told me that he was wrong - the story was worth doing.

The paper was gearing up to publish an ad-free 24-page supplement to run on December 7th. It would cost an extra $25,000 dollars to publish that had to be approved by the publisher. The word was spreading throughout Gannett (our owner) that this project “had Pulitzer written all over it.” I was not so confident.

Just a few days before going to print, James Gannon, the editor of the newspaper, called me into his office to offer some advice. He thought that the tone of the story was “too sad” for our readers, and wondered if I could race out there again and find a young farm family, just starting out, that had purchased a foreclosed farm and was “making a go of it.” I said,"I’ll think about it,” then walked out of his office and dismissed it! I did the layout and editing myself and insisted on it being published that way.

For the Pulitzer entry, I put the project together in a leather binder using 19 of my photos to tell the story, and also included the supplement. In late April of 1987, over five months after the project had been completed, I was driving back from Ottumwa, where I had done a freelance assignment for the National Geographic Kids Magazine. It was my day off from the newspaper. I had just gotten back into town, and had the radio on, tuned to a news station. It was 3 o’clock in the afternoon.

As the news was being read I heard my name over the radio … “If Dave Peterson feels like a Pulitzer Prize winner today, it’s because he is.” I didn’t hear the rest of what he said, but suddenly turned into a parking lot and starting driving the car in circles. I was in a state of disbelief. I kept saying “no” to myself, thinking that it couldn’t be true! There was a phone booth (remember those) in the lot, and I called the newspaper. One of the staff photographers answered and said “WHERE ARE YOU!” I drove to the paper, entered the newsroom to a standing ovation. I may have been the last person in Iowa to know that I had won a Pulitzer! -- David Peterson